Introduction

Disorders of gut-brain interaction (DGBI), formerly known as functional gastrointestinal disorders, are highly prevalent in the general population. They are characterized by chronic gastrointestinal symptoms without an evident organic cause and reflect an alteration in bidirectional brain-gut communication1.

Definition of functional dyspepsia

The Rome IV Consensus defines functional dyspepsia (FD) as the presence of one or more of the following symptoms: postprandial fullness, early satiation, epigastric pain or burning, without evidence of organic pathology that explains these symptoms following endoscopy, with a duration of 6 months, and symptoms present in the last 3 months2.

FD is classified into two subtypes: epigastric pain syndrome (EPS) and postprandial distress syndrome (PDS). It is the most common gastroduodenal disorder, and it should be noted that more than one-third of patients with FD present an overlap of EPS and PDS3.

Disorders of gut-brain interaction

DGBI are defined by the Rome IV criteria as a variable combination of chronic or recurrent gastrointestinal symptoms without evidence of structural or biochemical abnormalities to explain them. These symptoms originate from a complex interaction of multiple factors and result from alterations in gastrointestinal function due to a disorder in the bidirectional integration of the brain-gut axis1. In adults, DGBIs are grouped into 33 distinct disorders, classified according to six anatomical regions.

Overlap refers to the simultaneous presence of symptoms related to different regions of the gastrointestinal tract. The overlap of DGBIs is a very common phenomenon in clinical practice and has been extensively documented in the medical literature.

Prevalence and relevance of overlap

Variable percentages of overlap among DGBIs have been reported, depending on the population studied, the diagnostic criteria employed, and the methods used for data collection.

The global prevalence and associated factors of 22 types of DGBIs were investigated in 33 countries distributed across six continents, using the Rome IV and Rome III diagnostic questionnaires for the diagnosis of irritable bowel syndrome (IBS). This large-scale multinational study included 54,127 adults and revealed that more than 40% of people worldwide present with some DGBI. The second most frequent DGBI was FD, with a prevalence of 7.2%4.

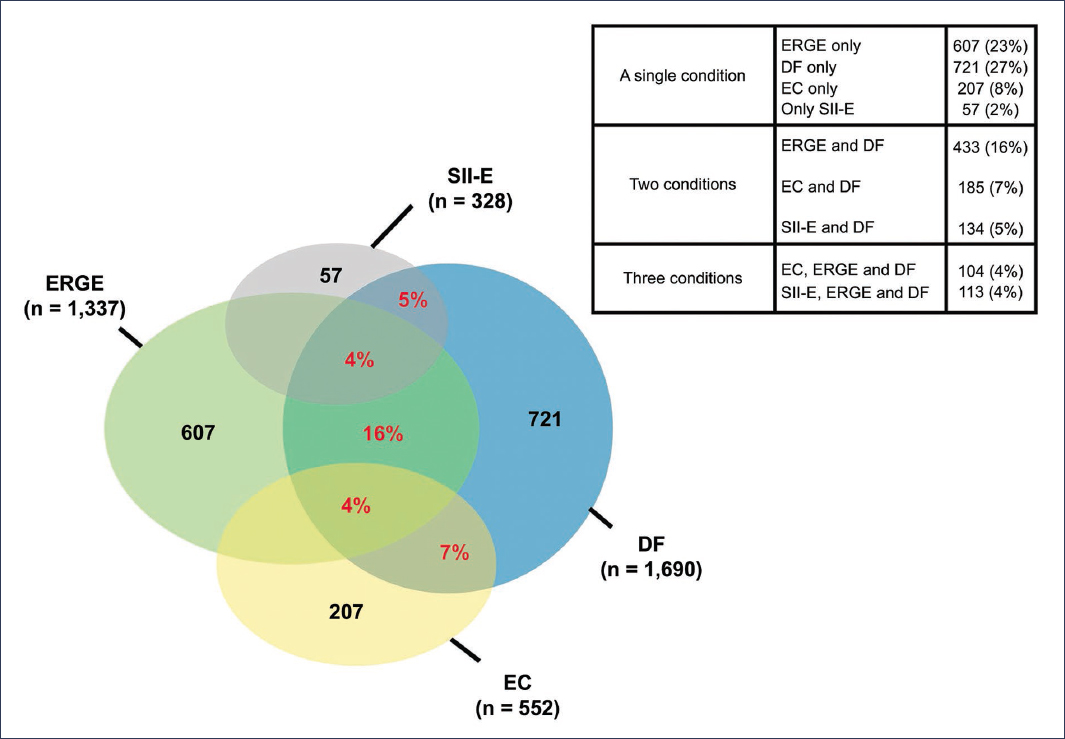

A population-based study investigated the overlap of specific DGBIs: FD, gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD), IBS with constipation (IBS-C), and chronic constipation (CC). The prevalence of FD was 27%. Among respondents, 60.3% reported having one condition, 31.5% indicated having two conditions, and 8.2% reported having three conditions5. Symptom intensity increased proportionally with the number of disorders present: 28.6% reported severe symptoms with a single condition, 50.7% with two conditions, and 69.6% with three conditions. The decrease in work productivity increased with the overlap of DGBIs. Likewise, a higher frequency of consultations in the last 12 months was observed: 43.7% in patients with one condition, 49.9% with two conditions, and 66.5% with three conditions. The most frequent overlap combinations were FD with GERD (16%), FD with CC (7%), and FD with IBS-C (5%) (Fig. 1).

Figure 1. Prevalence and overlap of disorders of gut-brain interaction. Overlap of functional dyspepsia (FD) with gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD), irritable bowel syndrome with constipation (IBS-C), and chronic constipation (CC) (adapted from Vakil et al.5).

In Mexico, the SIGAME 2 study (Gastrointestinal Symptoms in Mexico) was conducted, in which 1,000 patients who attended gastroenterology consultations in various states of the Republic were evaluated. The study identified an overlap of dyspepsia and GERD in 8.1% of cases, dyspepsia and IBS in 3.1%, and the coexistence of all three disorders in 3.1%. It is important to note that, in all cases of overlap of DGBIs, the prevalence was higher in women6.

In another study, conducted in a representative sample from three English-speaking countries, the prevalence and impact of overlapping DGBIs were evaluated according to the Rome IV criteria. Comparisons were made between individuals diagnosed with DGBIs, healthy controls, and patients with organic diseases. 35% of participants presented symptoms compatible with DGBIs. 36% of them had symptoms in more than one anatomical region, which was associated with higher levels of somatization, worse physical and mental quality of life, greater use of therapies, and more abdominal surgeries. Notably, these patients exhibited greater impairment in quality of life and more somatization than those with organic diseases7.

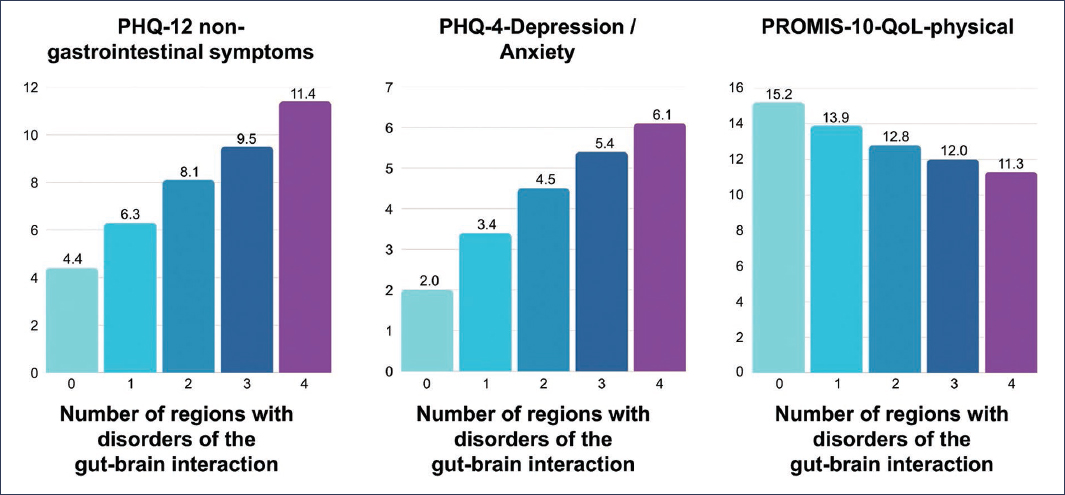

Many studies on the coexistence of DGBIs have been based on non-representative samples of the general population. In contrast, the aforementioned large-scale multinational study conducted in 26 countries was the subject of a second publication, whose primary objective was to evaluate the prevalence and impact of DGBI overlap. The study revealed that 40.3% of the surveyed individuals met the Rome IV criteria for some DGBI. The distribution according to the number of affected regions was as follows: 68.3% one region, 22.3% two regions, 7.1% three regions, and 2.3% four regions8. It was observed that somatization, anxiety, and depression increased significantly as the number of affected regions increased. Similarly, medical visits and medication use increased. Quality of life showed a progressive decline with increasing regional overlap of DGBIs (Fig. 2). As in other previous studies, it is emphasized that the presence of psychopathology is common in DGBIs affecting multiple regions and is associated with greater healthcare utilization.

Figure 2. Relationship between the number of affected regions in patients with overlapping disorders of gut-brain interaction with non-gastrointestinal symptoms (PHQ-12 somatization), anxiety and depression (PHQ-4), and quality of life (PROMIS-10-QoL-physical). Somatization, anxiety, and depression increase significantly as the number of affected regions increases. Quality of life showed a progressive decrease with increasing overlap (adapted from Sperber et al.8).

A systematic review and meta-analysis of 46 studies on DGBIs was conducted with the objective of comparing the prevalence of overlap between population-based studies, primary care studies, and tertiary care studies. The authors found that approximately one-third of participants presented DGBI overlap, with an overall prevalence of 36.5% (95% confidence interval [95% CI]: 30.7-42.6), although with considerable heterogeneity among studies. Overlap was more frequent in patients treated at tertiary care centers, with a prevalence of 47.3% (95% CI: 33.2-61.7), compared to studies conducted in the general population or primary care settings, where the prevalence was 26.5% (95% CI: 20.5-33.4). Furthermore, patients with overlap presented significantly lower quality of life, as well as higher prevalence of anxiety and depression9.

Functional dyspepsia and overlap with specific conditions

In a study conducted in China, consecutive patients who attended tertiary care centers and met the Rome IV criteria for FD were included. Standardized questionnaires were administered to assess GERD, anxiety, depression, quality of life, and sleep quality. Among patients with FD, 50.69% presented overlap with GERD, 21.46% with IBS, and 6.03% with CC10. The combined EPS/PDS subtype was most frequently associated with overlap with other functional disorders. This group presented a higher frequency of medical consultations, greater economic costs, and impaired quality of life. The following independent risk factors for FD overlap were identified: older age, female sex, low body mass index, history of gastroenteritis, anxiety, depression, and poor sleep quality.

Initial questionnaire-based studies have demonstrated that dyspeptic symptoms are more common in patients with frequent GERD symptoms, with a prevalence ranging from 21% to 63%, compared to those presenting with intermittent symptoms or who are asymptomatic11.

In a study that included 171 patients with GERD, it was observed that 28% presented overlap with FD according to the Rome III criteria. Patients with coexistence of GERD and FD tended to be younger and predominantly female. Furthermore, this group reported a more deteriorated quality of life compared to patients who only presented GERD or who had GERD overlapping with peptic ulcer12.

It has been reported that 23% of patients with FD present abnormal pH-metry13.

In a prospective study of a large cohort of patients with non-erosive GERD (NERD), a validated dyspepsia questionnaire was used, and pH-impedance studies were performed. It was found that clinically relevant dyspeptic symptoms were present in 44% of the patients. When classifying patients with NERD into three subgroups according to pH-impedance results, significant differences were observed in the frequency of dyspeptic symptoms (fullness and satiety): 63% in patients with functional heartburn, 41% in those with abnormal esophageal exposure (“true” NERD), and 37% in patients with hypersensitive esophagus. These findings suggest that the overlap between FD and GERD is more pronounced in the subgroup with functional heartburn14.

Within the complex pathophysiology of FD, emerging data point to the duodenum as a key integrator in the generation of dyspeptic symptoms. A case-control study conducted in Sweden included patients diagnosed with FD who underwent baseline endoscopy with duodenal biopsies, as well as administration of questionnaires. Ten years later, newly onset symptoms compatible with GERD were evaluated. The study found that duodenal eosinophilia at the time of diagnosis was associated with an increased risk of developing GERD at 10-year follow-up in patients with FD of the PDS subtype15. These findings suggest that duodenal eosinophilia could constitute a shared pathophysiological mechanism between FD and GERD, which supports the hypothesis that certain subtypes of both disorders could be part of the same clinical spectrum.

In clinical practice, the overlap between DGBIs, such as FD and IBS, may go unnoticed. A study investigated this situation through the use of diagnostic questionnaires, comparing the findings with the documentation recorded in medical records. It was found that 64% of patients presented overlap between FD and IBS according to the questionnaires, whereas it was documented in the clinical history in only 23%. Furthermore, symptom severity was significantly greater in patients with overlap between FD and IBS compared to those with a single diagnosis16. These results indicate that there is a clinical underestimation of the coexistence of DGBIs, which may lead to inadequate assessment and treatment.

Several studies have reported that the prevalence of FD and IBS in comorbidity ranges between 40% and 60%17. The coexistence of both disorders is typically characterized by the appearance of symptoms induced by food intake. It has been demonstrated that the increase in symptoms following a nutrient load correlates with visceral hypersensitivity, measured by rectal barostat, in patients with IBS.

In a prospective study, 205 patients with IBS were included, of whom 94 also met criteria for FD, and were compared with 83 healthy volunteers. The severity of gastrointestinal symptoms was assessed before and 15 minutes after the intake of a nutrient load and a lactulose breath test18. The results showed that patients with comorbid IBS and FD presented more intense symptoms at rest and postprandially, compared with patients with IBS alone. Furthermore, anxiety and somatization levels were associated with greater severity of postprandial symptoms. The prevalence of overlap between FD and IBS was 45.8%, which reinforces the hypothesis that, rather than separate conditions, FD and IBS could be clinical expressions of the same spectrum of DGBIs.

Studies have suggested that FD symptoms are present in 15.4% to 33.5% of patients with CD5. FD and IBS are two common functional disorders. Despite clear differences between them in terms of diagnostic criteria and treatment, there are common symptoms (such as abdominal pain and bloating) that may occur in both disorders. These shared symptoms may lead patients to erroneously attribute them to one condition or the other, depending on which appeared first or on the initial diagnostic approach.

In a study conducted at a tertiary-level neurogastroenterology clinic that included adults with refractory CC, the prevalence of overlap with FD, as well as gastrointestinal symptoms and associated clinical characteristics, was investigated. It was found that nearly 40% of patients with CC also met the diagnostic criteria for FD. This overlap was associated with a higher frequency of esophageal symptoms and abdominal distension, both objective and subjective. The high prevalence likely reflects the tertiary nature of the center, which serves patients seeking second or third opinions19. These findings suggest that unrecognized FD is common in patients with CC and persistent symptoms.

The coexistence of FBDs in patients with CC has been poorly studied. A study was conducted with the objective of investigating, in patients with CC, the prevalence and impact of FBDs on constipation severity and quality of life. Patients with CC according to Rome III criteria and patients diagnosed with dyssynergic defecation according to Rome IV were included, based on symptoms and physiological tests. It was found that 85% of patients with CC and dyssynergic defecation presented overlap with another FBD, with FD being the most common (41%)20.

The results demonstrate that this overlap has significant implications for the magnitude of symptoms and quality of life in patients with CD. Numerous studies support that FD and CD are simply different phenotypes of the same alteration in the brain-gut axis interaction21.

According to the Rome IV criteria, there are three disorders related to nausea and vomiting (NVD): chronic nausea and vomiting syndrome, cyclic vomiting syndrome (CVS), and cannabinoid hyperemesis syndrome2.

In a study that evaluated the prevalence of DGBI, FD, and IBS, the epidemiology, clinical characteristics, and associations of DGBI were analyzed. Of the population, 2.2% met the Rome IV criteria for DGBI, and the overlap with FD was 61.8%22.

In a multivariate analysis, the independent factors associated with NVD were younger age, greater severity of somatic symptoms, poor quality of life, and the presence of IBS and FD, compared with the control group.

Regarding the overlap between CVS and FD, patients with CVS frequently report digestive symptoms between vomiting episodes23. In a study that applied the Rome III questionnaires in patients with CVS, it was found that 66% met the criteria for FD. Dyspeptic symptoms are more frequent in patients with migraine and predict psychological distress in patients with CVS24.

Pathophysiological mechanisms of functional dyspepsia and overlap

In DGBIs, symptoms result from an alteration in the bidirectional gut-brain communication, involving multiple risk factors: genetic, environmental, and psychological. Triggering or symptom-exacerbating factors, such as gastroenteritis, food intolerances, and chronic stress. All of this leads to alterations in motility, visceral hyperalgesia, increased intestinal permeability, dysbiosis, and immune activation or low-grade inflammation1.

Although the pathophysiological basis of DGBIs is not yet fully understood, several mechanisms have been identified that could contribute to the high prevalence of overlap among these disorders. These mechanisms may involve different anatomical sites and, therefore, be relevant to multiple diagnoses defined by the Rome criteria.

Visceral hypersensitivity, frequently originating from central sensitization of visceral afferent signals in the brain-gut axis, is a key factor in determining symptom severity in DGBI, affecting both the upper and lower gastrointestinal tracts. Its presence could contribute significantly to the overlap of different disorders25. Likewise, alterations in the composition and function of immune cells have been observed in patients with IBS and FD, both systemically and in the mucosa26.

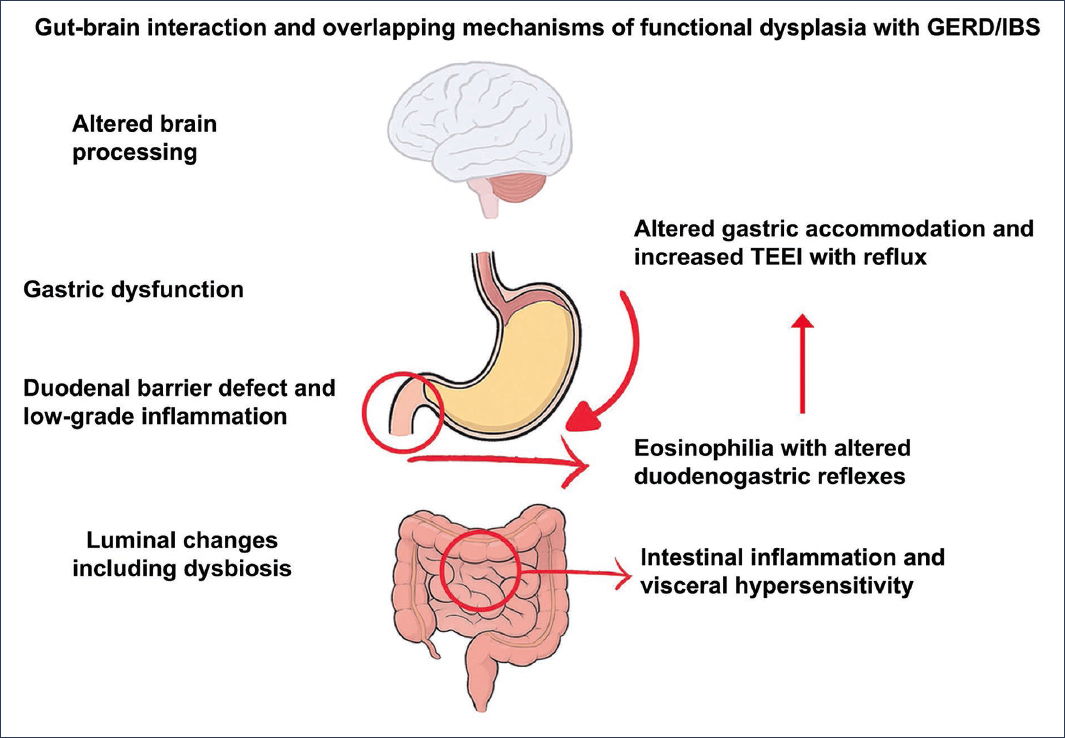

Wauters et al.27 highlight the role of the duodenum as a key integrator in the generation of dyspeptic symptoms (Fig. 3). Several studies have identified low-grade inflammation in the duodenal mucosa. The exact mechanism by which this inflammation produces neuronal hyperexcitability is not yet fully understood. An attractive hypothesis suggests that loss of mucosal integrity could be a primary event that triggers immune activation through antigen presentation, leading to eosinophil degranulation, which would cause visceral hypersensitivity and motor control dysfunction.

Figure 3. Gut-brain interaction and mechanisms involved in the overlap of functional dyspepsia (FD) with gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD) and irritable bowel syndrome (IBS). TLESRs: transient lower esophageal sphincter relaxations (adapted from Wauters et al.27).

It has been established that functional alterations in one segment of the gastrointestinal tract can influence the sensorimotor function of other segments. Altered motility in one part of the digestive tract may affect others, probably mediated by peptides or paravertebral neural reflexes28.

Through similar mechanisms, slow-transit constipation has been associated with impaired gastric accommodation, which is a key pathophysiological mechanism in FD29. This alteration in accommodation has also been linked to transient lower esophageal sphincter relaxations, which constitute the primary mechanism in gastroesophageal reflux episodes30.

Clinical approach to functional dyspepsia and overlap

Once the diagnosis of FD has been established according to the Rome IV criteria, a systematic evaluation of the symptom pattern through a detailed clinical interview is recommended. This process should be oriented toward identifying the possible coexistence of other DGBIs that suggest an overlap syndrome.

The quality of the anamnesis depends largely on the clinician’s skills and their ability to establish effective communication with the patient. However, discrepancies may exist between the patient’s subjective perception and the medical interpretation of symptoms31. Even with a structured clinical interview conducted by an experienced physician, symptoms may not be expressed clearly or comprehensibly due to their individual and multidimensional nature. In these cases, the use of pictograms accompanied by verbal descriptions has been shown to significantly improve symptom identification, facilitating the recognition of overlap and the determination of the predominant or most bothersome symptom32.

The use of self-administered questionnaires in the waiting room, which include symptom descriptions and pictograms for the main DGBIs, represents a useful and promising tool for improving diagnostic accuracy.

It is important to note that the overlap of DGBIs may manifest in two ways: in different anatomical regions of the gastrointestinal tract or within the same region; for example, the coexistence of PDS with EPS, which are considered distinct diagnoses according to Rome IV criteria2.

In cases of overlap, it is essential to identify the temporal relationship between symptoms. The clinical history should explore whether these symptoms appear simultaneously, or worsen or improve together, or occur independently. It is also clinically relevant to assess the relationship of symptoms with triggering factors, such as food intake, belching, passage of gas or defecation, or with emotional or psychological events.

As previously mentioned, the assessment of psychological comorbidity is essential. Factors such as anxiety, depression, and somatization can amplify the perception and reporting of symptoms, which increases the likelihood of overlap among different DGBIs. This comorbidity constitutes an essential component of the patient’s multidimensional clinical profile, and its identification is critical for an effective therapeutic approach. These aspects can be explored both during the clinical history-taking and through the use of validated instruments, such as the Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale4.

Diagnostic studies in patients with overlap

Although the overlap of DGBIs is highly prevalent in clinical practice, most diagnostic guidelines are designed for patients with a single functional disorder. Currently, there are no specific guidelines that systematically guide the selection of diagnostic studies in cases of overlap31.

One of the fundamental steps is the assessment of alarm features, which determine the need for and extent of additional studies, according to international consensus recommendations3. It is important to emphasize that the presence of multiple symptoms does not automatically justify the performance of additional tests.

In patients with overlapping DGBI, diagnostic complexity and the possibility of an incomplete therapeutic response are greater. However, the clinical yield of complementary studies, such as repeated endoscopies, imaging tests, or sophisticated functional examinations, is usually low in the absence of alarm features31. In these cases, the diagnosis of DGBI (or their overlap) can be established positively, provided that the Rome IV clinical criteria are met and organic diseases have been ruled out with a limited diagnostic approach, as indicated by the relevant international guidelines33. A well-structured clinical approach enables the physician to improve the quality of care, avoid unnecessary interventions, and optimize health outcomes.

Treatment

The presence of overlap among DGBIs does not necessarily imply the initial combined use of multiple drugs. Treatment should be based on the clinical evaluation of the symptom pattern and identification of the predominant functional disorder. The therapeutic objective should focus on the most bothersome or priority symptom for the patient. To date, no studies support a standardized treatment regimen for all cases of overlap.

Likewise, the identification of psychological comorbidity, such as anxiety, depression, and somatization, may be key to optimizing the therapeutic approach, particularly in cases of FD coexisting with other DGBIs31.

Conclusions

DGBIs present a high prevalence in the population, and one-third of patients show symptom overlap. FD, also of high prevalence, can coexist with GERD, IBS, CC, and FV. This overlap is associated with greater symptom severity, increased psychological burden, impaired quality of life, and greater use of healthcare resources.

In patients with FD, it is essential to identify the presence of other DGBIs that may indicate overlap. Likewise, the existence of anxiety, depression, and somatization should be evaluated, as their treatment is key in the comprehensive management of the patient. The presence of multiple symptoms does not imply the need to perform additional studies. The coexistence of various DGBIs represents an additional challenge in establishing an appropriate therapeutic plan.

Funding

The authors declare that they have not received funding for this study.

Conflicts of interest

M.A. González-Martínez is a speaker for Grunenthal. J.P. Ochoa-Maya has no conflicts of interest.

Ethical considerations

Protection of human and animal subjects. The authors declare that no experiments have been conducted on human subjects or animals for this research.

Confidentiality, informed consent, and ethical approval. The study does not involve patient personal data nor does it require ethical approval. The SAGER guidelines do not apply.

Declaration on the use of artificial intelligence. The authors declare that they did not use any type of generative artificial intelligence for the writing of this manuscript.