Introduction

The term “dyspepsia” derives from the Greek words δυς- (dys-) and πέψη (pepse), which translate as “difficult digestion”1. When referring to dyspepsia, it generally denotes pain of gastroduodenal origin that has certain characteristics, which are detailed throughout the chapter. The prevalence of dyspepsia varies according to country and the criteria used for its diagnosis; it is estimated that up to 20.8% of the general population presents with it, but further studies with standardized methodology are needed2.

In the present article, we review the general aspects of dyspepsia, with emphasis on the diagnostic approach to FD.

Definition of dyspepsia and functional dyspepsia

It is important to distinguish between dyspepsia as a symptom and the diagnosis of FD. Dyspeptic symptoms are defined by the American College of Gastroenterology as epigastric pain of at least 1 month’s duration, which may or may not be associated with epigastric fullness, nausea, or vomiting3. To establish the diagnosis of FD, it is essential to exclude organic pathologies as the cause of the symptoms.

Physical examination has not proven to be sufficiently accurate to distinguish between organic dyspepsia and FD4, thus diagnostic studies are necessary to differentiate them3. Upper endoscopy is recommended in patients with uninvestigated dyspepsia aged > 55-60 years, with alarm symptoms or signs (unintentional weight loss, gastrointestinal bleeding, dysphagia, persistent vomiting, iron deficiency anemia, epigastric mass), to rule out structural causes, although even with the presence of these symptoms, the possibility of malignancy remains low5. This was demonstrated by Ford et al.6 in a systematic review and meta-analysis, finding that of the total patients studied for dyspepsia who underwent upper endoscopy, 72.5% had no abnormalities, 20% had erosive esophagitis, 6% had peptic ulcer, 1.1% had Barrett’s esophagus, and only 0.4% had gastroesophageal cancer.

Epidemiology

The global prevalence of uninvestigated dyspepsia (Rome III criteria) is 20.8%2, with significant variation according to geographic area; thus, in South America, 37.7% was reported, in Africa 35.7%, in Southern Europe 24.3%, in North America 22.1%, in Northern Europe 21.7%, in Australia 20.6%, in Eastern Europe 15.2%, in Southwest Asia 14.6%, and in Central America 7%. In 2012, a Mexican study revealed that the prevalence of this condition was 8%7.

In 2018, a study was conducted in Canada, the United States, and the United Kingdom, which reported a prevalence of FD (Rome IV Criteria) of 8%, 12%, and 8%, respectively8. The prevalence of FD was higher in females. The authors mention that the difference in prevalence among countries may be due to genetic, cultural, socioeconomic, dietary, and environmental factors8.

The Mexican consensus on FD reports a prevalence of 6.9% in Argentina, 7.2% in Colombia, 6.59% in Mexico, and 10.6% in Brazil9,10.

Diagnostic criteria for functional dyspepsia: the rome consensus through time

In the 1980s, multinational groups emerged seeking the homogenization of functional gastrointestinal disorders, which constituted the basis for establishing the Rome criteria11.

The Rome I and II Consensus defined dyspepsia as upper abdominal pain, postprandial fullness, upper abdominal distension, early satiety, epigastric burning, nausea, vomiting, and belching11,12. The Rome III Consensus excluded some symptoms and defined postprandial fullness, early satiety, epigastric pain, and epigastric burning as gastroduodenal symptoms suggestive of dyspepsia; in this consensus, the terms “ulcer-like dyspepsia,” “dysmotility-like dyspepsia,” and “nonspecific dyspepsia” were discontinued, and postprandial distress syndrome and epigastric pain syndrome were introduced13. The most recent Rome Consensus (IV), in 2016, established that FD is characterized by the presence of at least one of the following symptoms: early satiety, epigastric pain, postprandial fullness, and epigastric burning. The symptoms must have been present during the last 3 months and have started within the previous 6 months. Furthermore, the exclusion of organic disorders as a cause of dyspepsia is mandatory14 (Table 1). Currently, the Rome Foundation is in the process of developing the Rome V criteria, with publication planned for 2026.

Table 1. Rome IV Criteria for Functional Dyspepsia

| Entity | Diagnostic criteria | Supporting notes/Data |

|---|---|---|

| Functional dyspepsia (FD) | One or more of the following: – Bothersome postprandial fullness – Early satiation – Epigastric pain – Epigastric burning No evidence of structural disease to explain the symptoms (including endoscopy) Symptoms present for ≥ 3 months, with onset ≥ 6 months before diagnosis |

For classification: – Postprandial distress syndrome (PDS) – Epigastric pain syndrome (EPS) |

| B1a. Postprandial distress syndrome (PDS) | At least 1 of the following ≥ 3 days/week: – Bothersome postprandial fullness (interferes with usual activities) – Bothersome early satiation (prevents finishing a normal-sized meal) Without organic, systemic, or metabolic disease to explain it Symptoms present for the last 3 months, with onset ≥ 6 months prior |

The following may coexist: epigastric pain/burning, epigastric bloating, excessive belching, nausea Heartburn is not a dyspeptic symptom (may coexist) Symptoms relieved by defecation or passing gas are not FD May coexist with GERD or IBS |

| B1b. Epigastric pain syndrome (EPS) | At least 1 of the following ≥ 1 day/week: – Bothersome epigastric pain (interferes with usual activities) – Bothersome epigastric burning (interferes with usual activities) Without structural disease to explain it (including endoscopy) Symptoms present for the last 3 months, onset ≥ 6 months prior. |

The pain may be induced or alleviated by food, but it can occur during fasting. The following may coexist: epigastric distension, belching, nausea. Heartburn is not a dyspeptic symptom (although it may coexist). The pain must not meet criteria for biliary pain. Other symptoms (GERD, IBS) may coexist. |

|

Adapted from Stanghellini et al.32 |

||

PAGI-SYM questionnaire

In 2004, a self-assessment questionnaire known as the Patient Assessment of Upper Gastrointestinal Disorders-Symptom Severity Index (PAGI-SYM) was developed for the evaluation of patients with upper gastrointestinal disorders15. To this end, a study included 767 patients with FD (nausea, early satiety, postprandial fullness, nausea with or without symptoms, and epigastric pain, according to Rome II criteria). The PAGI-SYM questionnaire has demonstrated excellent reproducibility, which positions it as a useful tool in both clinical practice and research. Internal consistency indicated a high correlation among the elements comprising each symptomatic subscale; furthermore, test-retest reliability reflected adequate temporal stability of the scores. These psychometric properties support the use of PAGI-SYM as a standardized instrument to quantify symptom severity in FD and to assess treatment response in clinical trials or longitudinal follow-up16.

Although the PAGI-SYM questionnaire does not have a defined diagnostic cutoff value for FD, it has been established that a reduction of at least 0.6-0.7 points in key subscales (such as postprandial fullness, early satiety, or epigastric pain) represents clinically significant changes, which allows for objective assessment of the efficacy of therapeutic interventions. table 2 shows the Spanish version of this questionnaire17.

Table 2. PAGI-SYM Questionnaire in Spanish

| Symptoms | Degree of involvement | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Burning pain sensation in the chest or throat during the day | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

| 2. Liquid regurgitation rising from the stomach to the throat during the day | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

| 3. Nausea sensation in the stomach as if ready to vomit | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

| 4. Abdominal pain in the upper area above the umbilicus | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

| 5. Stomach fullness | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

| 6. Loss of appetite | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

| 7. Abdominal discomfort in the upper area above the umbilicus | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

| 8. Bloating: sensation as if needing to loosen clothing | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

| 9. Heartburn: burning pain that goes from the chest or throat toward the abdomen | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

| 10. Regurgitation of liquid from the stomach to the throat | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

| 11. Abdominal pain in the lower abdomen (below the umbilicus) | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

| 12. Discomfort sensation inside the stomach that lasts all day | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

| 13. Bitter or sour taste in the mouth | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

| 14. Abdominal discomfort below the umbilicus | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

| 15. Discomfort sensation inside the chest during the night (while sleeping) | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

| 16. Urge to vomit without vomiting occurring | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

| 17. Visibly swollen stomach or abdomen | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

| 18. Vomiting | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

| 19. Being unable to finish eating a complete lunch | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

| 20. Feeling completely full after meals | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

|

Severity scale: 0 = none, 1 = very mild, 2 = mild, 3 = moderate, 4 = severe, 5 = very severe. |

||||||

Pictograms

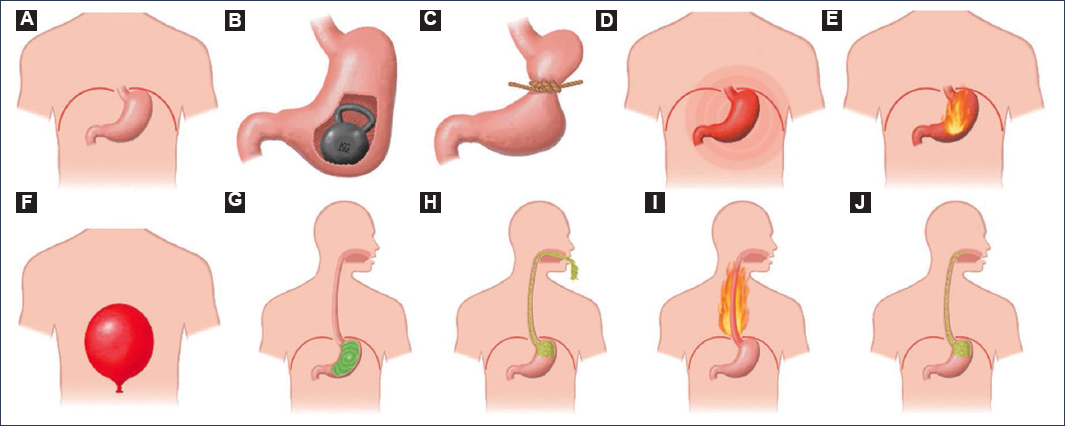

Given that patients’ perception of their symptoms is fundamental for correctly identifying the predominant symptom, visual tools such as pictograms have been developed to facilitate physician-patient communication.

Tack et al.18 proposed a pictogram model (Fig. 1) based on the Dyspepsia Symptom Severity Index and the PAGI-SYM questionnaire. In their study, they recruited patients diagnosed with FD aged between 18 and 70 years who met the Rome III criteria. The objective was to evaluate whether the addition of pictograms to verbal descriptions improved symptom comprehension and assessment. The results were compelling, as the overall concordance between symptom assessments performed by the patient and by the physician increased from 36% to 48% when pictograms were included. This improvement was notable in symptoms such as abdominal distension and epigastric burning, in which agreement was significantly higher with the use of pictograms; however, no additional benefit was observed in the assessment of nausea and vomiting. The use of visual representations facilitated the distinction between symptoms that are often confused, such as epigastric burning versus retrosternal heartburn, or postprandial fullness versus abdominal distension.

Figure 1. Pictograms facilitating the identification of conditions in subjects with dyspepsia. A: stomach location. B: postprandial fullness. C: early satiety. D: epigastric pain. E: epigastric burning. F: upper abdominal distension. G: nausea. H: vomiting. I: heartburn. J: regurgitation (adapted from Tack et al.18).

In 2023, Schmulson et al.19 conducted a study in Mexico using the Rome IV criteria, in which they explored the term “bloating” in English and “hinchazón” in Spanish. They compared oral descriptions with the use of pictograms and reported that pictograms were superior for describing the symptoms of bloating and distension19.

These findings suggest that the incorporation of pictograms may improve the accuracy with which patients communicate their symptoms, and could represent a useful advancement both in clinical practice and in the design of clinical trials on FD.

Characteristics and risk factors of functional dyspepsia

Various factors have been described as associated with FD, including female sex, tobacco use, nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drug (NSAID) use, elevated body mass index (BMI), psychological conditions, ethnic differences, postinfectious dyspepsia (gastroenteritis), high-fat food consumption, socioeconomic differences, and Helicobacter pylori infection20.

Arnaout et al.21 conducted an analysis of 5,506 patients from 15 different countries, with the objective of reporting the prevalence and risk factors associated with FD. They identified age > 60 years, female sex, elevated BMI, presence of comorbidity, and rural residence as risk factors associated with FD. Comorbidity included hypertension, diabetes mellitus, autoimmune diseases, migraine or headache, anemia, asthma, ischemic heart disease, history of COVID-19, and endometriosis. History of abdominal surgery, coffee consumption, more than 8 hours of sleep, smoking, work in information technology, computer engineering, teaching, and economics, and exposure to high levels of stress were also associated.

Wang et al.22 conducted a retrospective study that included 8,875 cases of FD and 320,387 controls. They performed a systematic search for risk factors for FD and identified the following: anxiety, depression, somatization, sleep disorders, high-fat food intake, frequent consumption of ultra-processed foods, smoking, metabolic dysfunction-associated steatotic liver disease, female sex, NSAID use, H. pylori infection, overweight and obesity, history of acute gastroenteritis, consumption of spicy foods, low socioeconomic status, constipation, diabetes mellitus, alcohol consumption, irritable bowel syndrome, thyroid diseases, and caffeine consumption. The coexistence of FD with other disorders of the brain-gut axis, such as gastroesophageal reflux disease, functional constipation, and irritable bowel syndrome, is common23. Long et al.24 described that the risk factors for presenting overlap of FD with other disorders of the brain-gut axis are female sex, history of gastroenteritis, anxiety, depression, and impaired sleep quality.

Pathophysiology of functional dyspepsia

The pathophysiology of FD is not completely understood, but several mechanisms have been proposed that could explain its clinical manifestations. Among the most studied are alterations in gastric motility, visceral sensitivity, gastric mucosal integrity, and the brain-gut axis interaction.

In patients with postprandial distress syndrome, alterations such as reduced gastric accommodation, antral overload, inhibition of the gastric relaxation reflex, and delayed gastric emptying have been described; all of these contribute to the sensation of early satiety and abnormal fullness20,25.

Gastric mechanical hypersensitivity has been associated with symptoms such as epigastric pain, postprandial fullness, abdominal distension, and belching. Chemical hypersensitivity, attributed to increased sensitivity to gastric acid (exogenous and endogenous), is primarily associated with nausea20.

In molecular studies, the involvement of the transient receptor potential vanilloid 1 receptor has been identified, which is activated by capsaicin, mechanical stimuli, inflammatory mediators, acid, prostaglandins, microorganisms, and growth factors. Its activation induces the release of neuropeptides, such as substance P and calcitonin gene-related peptide, which could amplify gastric sensitivity and the inflammatory response26–28. A decrease in the expression of immunoregulatory molecules has also been reported, such as Fas ligand and the HLA-DRA gene, involved in cellular apoptosis, lymphocyte homeostasis, and B cell regulation, suggesting local immune dysfunction20. In this regard, the presence of eosinophilia and increased duodenal permeability have been linked to postprandial distress symptoms, reinforcing the hypothesis of low-grade inflammation20,25,29,30.

Furthermore, intestinal dysbiosis, especially in the duodenum, has been associated with worse quality of life and more intense symptoms in FD. Alterations in the composition of the microbiota, changes in bile acid metabolism, and the proliferation of proinflammatory bacteria could promote chronic inflammation and epithelial barrier dysfunction20,31.

Finally, a dysfunction in the brain-gut axis has been identified, involving factors such as stress, immune activation, intestinal barrier disruption, and the microbiota. These alterations can modulate both visceral perception and the patient’s emotional state through neuroendocrine pathways and neurotransmitters20,31.

The role of endoscopy in functional dyspepsia

The definition of dyspepsia has undergone significant changes over time. Whereas early definitions included symptoms such as epigastric burning, nausea, vomiting, and belching within the dyspeptic symptom complex, the Rome III and IV Consensus have significantly reduced the symptom profile13,32,33. The Rome IV Consensus defined dyspepsia as the presence of chronic symptoms originating in the gastroduodenal region32. According to this consensus, the four cardinal symptoms of dyspepsia are postprandial fullness, early satiation, epigastric pain, and non-radiating epigastric burning32.

Specifically, FD is defined as the presence of chronic dyspeptic symptoms in the absence of an organic disease that explains them32. Symptoms do not reliably distinguish between FD and organic dyspepsia32,34. Consequently, in clinical practice, upper endoscopy is performed to rule out organic causes. The prevalence of clinically significant endoscopic findings in subjects with uninvestigated dyspepsia is low, but the high number of affected patients is not negligible. Fewer than 10% of patients have a peptic ulcer, and fewer than 1% have gastroesophageal cancer6. Thus, based on endoscopic findings, a systematic review and meta-analysis found that more than 70% of subjects with dyspeptic symptoms meet the criteria for a diagnosis of FD6.

Therefore, current guidelines suggest performing upper endoscopy for patients aged 60 years or older to rule out malignancy; however, it is not recommended to routinely perform it to exclude malignancy in patients younger than 60 years, as their cancer risk is low even in the presence of alarm symptoms3. For patients younger than 60 years, noninvasive testing for H. pylori, such as stool antigen testing, is recommended3,35.

Functional dyspepsia versus gastroparesis

It is essential to distinguish patients with FD from those presenting with gastroparesis, and to better understand the relationship between symptoms, gastric emptying, and the alteration of peripheral and central sensory responses to gastric stimuli. To differentiate these pathologies, various diagnostic modalities are used.

The differential diagnosis consists of two steps36. First, mechanical obstruction must be excluded using imaging techniques (preferably upper endoscopy and Vcomputed tomography or magnetic resonance enterography). Second, motility abnormalities should be evaluated using gastric emptying scintigraphy or antroduodenal manometry.

Although several methods exist for objectively measuring gastric emptying, solid-meal gastric emptying scintigraphy is the reference standard37. The joint standardized criteria of the American Neurogastroenterology and Motility Society and the Society of Nuclear Medicine establish that gastric retention > 90% at 1 h, > 60% at 2 h, > 30% at 3 h, and > 10% at 4 h is diagnostic of delayed gastric emptying38. However, it has been described that symptoms do not correlate with the severity of delayed gastric emptying or with the response to prokinetics39.

The fundamental problem in distinguishing between FD and gastroparesis is that delayed gastric emptying may be present in up to 25% of patients with FD. In light of this, some authors have proposed that the definition of gastroparesis should be more stringent (> 60% of food retained after 4 hours), although its incidence would decrease considerably40.

Another option for assessing gastric emptying time is the carbon-13 breath test41. Numerous studies have validated the ability of the breath test to quantify gastric emptying42. It should be noted that certain hepatic and pulmonary diseases may affect CO2 metabolism and, consequently, the test results.

Another diagnostic test is the wireless motility capsule, which measures pressure, temperature, pH, and motility (gastric, intestinal, and colonic). Using a cutoff of 5 hours for gastric emptying, the capsule can differentiate normal from delayed gastric emptying with a sensitivity of 87% and a specificity of 92%13. In a study comparing the wireless motility capsule and gastric emptying scintigraphy, the correlation was 73% at 4 hours43. Therefore, these three tests are valid modalities for the diagnostic evaluation of gastroparesis.

Antroduodenal manometry helps differentiate the neuropathic or myopathic origins of gastroparesis44. This test determines the presence of the migrating motor complex. In patients with neuropathies, uncoordinated contractions of normal amplitude are detected, whereas low-amplitude or completely absent contractions suggest a myopathic origin. In patients with type 1 or type 2 diabetes mellitus, phase III of the migrating motor complex is usually abolished. Unfortunately, this test is limited to few centers and is poorly tolerated by patients.

The gastric barostat is a standard method for the assessment of gastric accommodation; however, it is invasive and poorly tolerated in clinical practice.

Recently developed techniques, such as positron emission tomography, three-dimensional ultrasonography, and magnetic resonance imaging, can measure gastric volumes and are promising alternatives for the noninvasive assessment of gastric accommodation45,46.

New assessment techniques in functional dyspepsia

Water intake tests

The water drinking test was initially developed as a provocation test to investigate symptomatic patterns and the capacity to tolerate a specific volume of liquid in the stomach of patients with FD. In the initial application of the test, 24 patients with FD and 24 healthy volunteers were instructed to freely consume still water at room temperature within a 5-minute period. Simultaneously, upper gastrointestinal symptoms were documented using symptom assessment questionnaires. The results showed that patients with FD tolerated smaller amounts and obtained higher scores for symptoms of fullness, satiety, bloating, and nausea47.

The rapid water drinking test, which consists of ingesting 100 ml of water per minute until reaching the highest discomfort score or maximum water intake within a 5-minute period, is simple and appears to be reproducible; however, it is susceptible to sex-related variations. The disadvantages of the rapid water drinking test are its non-physiological methodology, the use of a non-caloric stimulus, and the fact that the subject is aware of the volume ingested48.

Boeckxstaens et al.48 conducted a study in which the rapid water drinking test was applied to 25 healthy subjects and 42 patients with FD. After each intake of 100 ml, upper gastrointestinal symptoms were evaluated. In particular, patients with FD showed lower tolerance to larger volumes and reported higher and more persistent symptom scores during the test48.

Rapid nutritive beverage consumption test

In the study by Boeckxstaens et al.48, the nutrient drink test was also used to assess patients with FD. Both patients with FD and healthy subjects consumed 100 ml of nutrient drink until reaching a discomfort score of 5. The ingestion pattern was similar to that of the rapid water drinking test. In this study, patients with FD demonstrated lower tolerance compared to healthy subjects, while also reporting higher and more persistent symptom scores during the test. These results are consistent with those of the rapid water intake test, but the tolerated volume of nutrient drink was notably lower.

Satiety test and slow nutrient drink test

The initial presentation of a slow nutrient infusion test dates back to 199849. The test was designed to assess gastric accommodation non-invasively. It consists of the patient consuming a liquid mixed-nutrient drink administered through an infusion pump at a gradual and constant rate until reaching the maximum satiety score, denoted as 5 out of 6 on a 0-6 Likert satiety scale50. In the initial report on the test, patients with FD drank significantly less than healthy subjects. The result was associated with impaired gastric accommodation, but not with decreased gastric emptying rate51. To reveal the impact of caloric density (1.5-2.0 kcal/ml) on the test, Tack51 demonstrated that even with the intake of a higher-calorie drink, satiety scores did not differ significantly. These observations indicate that the test is intrinsically governed by volume, consistent with its purpose of quantitatively assessing gastric accommodation.

Another assessment method is the slow nutrient ingestion test51. Kindt et al.52 evaluated the reproducibility of this test in 78 patients with FD and 34 healthy controls. The maximum amount ingested was significantly lower in patients with FD. The reproducibility of the test was excellent, which identifies its potential role as a non-invasive tool for diagnosing gastric accommodation disorders and for evaluating treatment response.

Drink test and ultrasonography

Hata et al.53 conducted a study to evaluate gastric motor and sensory functions using a drinking test and ultrasonography, including 20 healthy subjects and 26 patients with FD diagnosed according to the Rome III criteria.

The drinking and ultrasonography test was performed after a minimum fasting period of 6 hours. During the drinking phase, subjects consumed 200 ml of water at 2-minute intervals, repeated four times (800 ml in total). The test ceased when subjects felt unable to ingest more. The evaluation of the emptying period took place 5 and 10 minutes after consuming 800 ml or after discontinuing the test, which marked the end of the procedure. The transverse view of the proximal stomach was observed by extracorporeal ultrasonography, using the tenth intercostal space with the spleen as an acoustic window. The measurement of the maximum cross-sectional area of the proximal stomach was performed before water intake and after each 2-minute interval of water consumption, and 5 and 10 minutes after completion of the test. After freezing the image, the ultrasonography system was used to delineate the mucosal surface of the gastric lumen, and subsequently, the cross-sectional area was calculated. During the water consumption period, abdominal symptoms were evaluated on five occasions. Participants were specifically asked about any impediment to drinking attributed to symptoms such as abdominal fullness and epigastric pain. The study results showed that the mean cross-sectional area of the gastric fundus after ingestion of 800 ml of water was notably reduced in the FD group compared to the control group. Although no statistically significant differences were observed between the two groups, the mean value of the fundic cross-sectional area in the FD group exceeded that of the control group, indicating a possible delay in emptying in individuals with FD. In the FD group, notable symptoms such as abdominal fullness and epigastric pain manifested immediately after initiating water intake. The symptom score showed a significant difference between the control group and the FD group at each evaluation time point, indicating greater sensitivity in patients with FD53.

Functional magnetic resonance imaging

Functional magnetic resonance imaging is a technique used to analyze regional alterations in oxygenation and blood flow within the brain. It detects changes in the volume of active brain regions through BOLD (blood oxygen level-dependent) signals, which indicate the relationship between magnetic resonance signal intensity and blood oxygenation levels. Variations in these signals occur due to fluctuations in deoxyhemoglobin levels, which may arise from changes in cognitive states during tasks or during rest periods54. Patients with FD present various irregularities in specific brain regions. Vandenberghe et al.55 conducted a study in 16 patients with FD in whom they used gastric balloons and observed abnormal activity in several brain areas, including the precentral gyrus (bilaterally), the inferior frontal gyrus (bilaterally), the middle frontal gyrus, the superior temporal gyrus, both cerebellar hemispheres, and the inferior temporal gyrus on the left side.

Conclusions

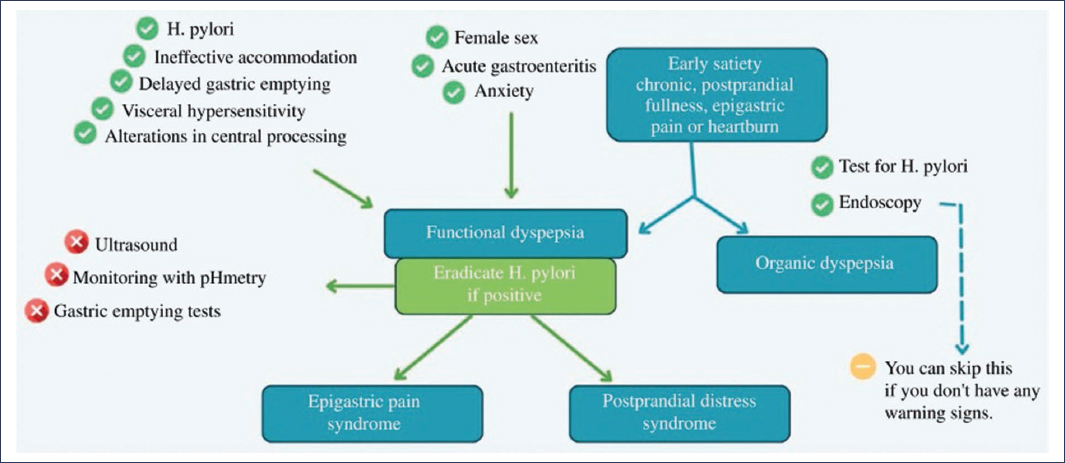

In conclusion, FD represents a complex diagnosis that requires careful exclusion of organic diseases, guided by the Rome IV criteria and by tools such as the PAGI-SYM questionnaire.

Fig. 2 summarizes the proposed clinical approach. This systematic approach allows for better classification and personalized management of the patient with dyspepsia.

Figure 2. Summary of the approach and classification of dyspepsia (adapted from United European Gastroenterology (UEG) and European Society for Neurogastroenterology and Motility (ESNM) consensus on functional dyspepsia56).

Funding

The authors declare that they have not received funding for this study.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Ethical considerations

Protection of human and animal subjects. The authors declare that no experiments have been conducted on human beings or animals for this research.

Confidentiality, informed consent, and ethical approval. The study does not involve patient personal data nor does it require ethical approval. The SAGER guidelines do not apply.

Declaration on the use of artificial intelligence. The authors declare that they did not use any type of generative artificial intelligence for the writing of this manuscript.