Introduction: pathophysiological differences between functional dyspepsia subtypes

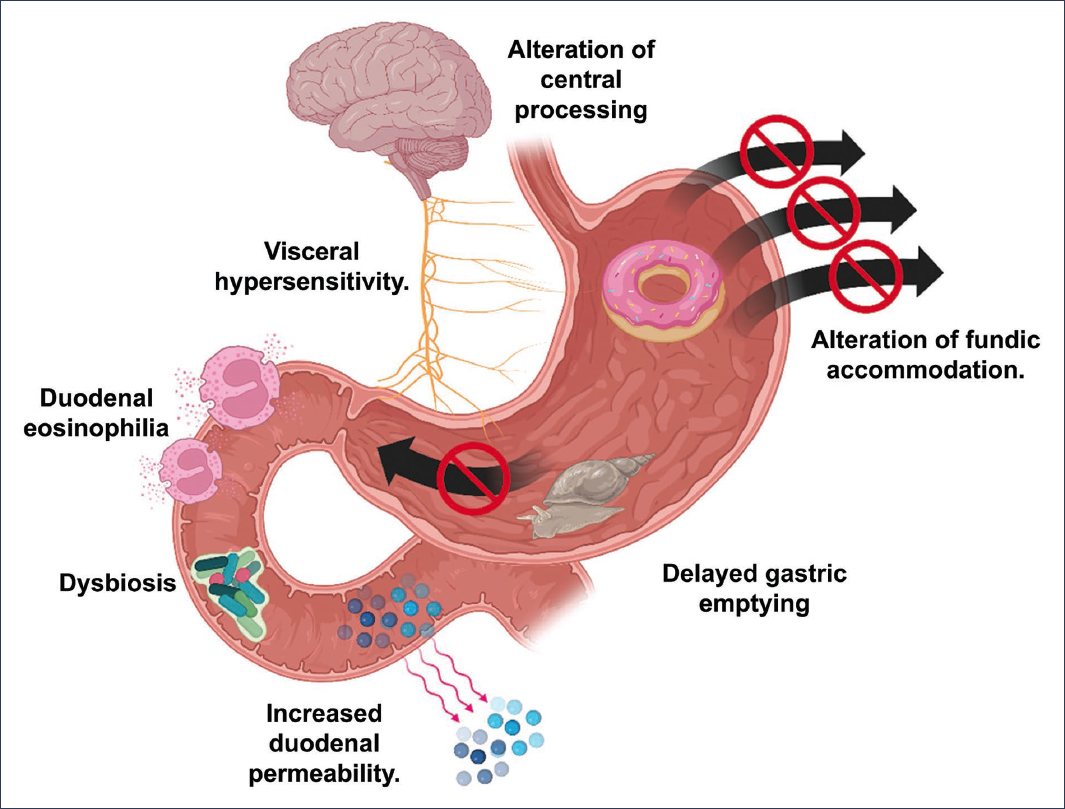

The pathophysiology of functional dyspepsia (FD) is considered multifactorial, resulting in a heterogeneous disorder in which different underlying pathophysiological mechanisms are associated with different symptom profiles. The pathophysiology of FD (Fig. 1) includes gastric abnormalities, such as delayed gastric emptying, impaired fundic accommodation, hypersensitivity to gastric distension, and hypersensitivity to duodenal acid and lipid concentration, as well as a role for activated eosinophils, since a causal link has been established between eosinophils and intestinal dysmotility. It is impossible to identify a unified pathological mechanism that explains the symptoms of all patients with FD, which include changes in the stomach (impaired regulatory function, delayed gastric emptying, and allergies) and changes in the duodenum (increased duodenal acid or lipid sensitivity and mild inflammation). These functional and structural abnormalities may interact and are involved in the impairment of mucosal integrity, immune barrier dysfunction, and abnormal regulation of the gut-brain axis1,2.

Figure 1. Pathophysiology of functional dyspepsia (created with BioRender.com).

Visceral hypersensitivity and alterations in gastric motility

Impaired gastric accommodation and delayed gastric emptying are fundamental pathophysiological mechanisms in FD. Gastric accommodation is impaired in 15-50% of patients, which is associated with reduced capacity for liquid intake, early satiety, postprandial fullness, and weight loss. In turn, gastric emptying in patients with FD can be up to 1.46 times slower than in healthy controls and has been associated with female sex, nausea, vomiting, and early satiety.

Patients with FD also exhibit reduced duodenal motor activity in response to acid perfusion, which promotes greater exposure to duodenal acid. This alteration may be linked to decreased vagal efferent function, suggesting that the vagus nerve plays an essential role in the control of upper gastrointestinal motility. The degree of gastric sensory and motor dysfunction determines the severity of clinical symptoms. Hypersensitivity to gastric distension has been documented in 34-65% of patients with FD, and symptoms are more pronounced in the postprandial period than during fasting, which has been attributed in part to delayed duodenal acid clearance. Hypersensitivity to luminal chemical stimuli, such as acid and lipids, has also been described, resulting in a diminished duodenal motor response. It is worth noting that altered vagal tone is associated with delayed gastric emptying, and impaired duodenal function could also contribute to proximal gastric dysfunction, affecting both accommodation and emptying. It has been demonstrated that patients with FD present decreased thresholds for pain perception during proximal stomach distension, which evidences significant visceral hypersensitivity. This may be due to sensitization of nociceptive pathways, multimodal pathways, or both, resulting in greater intensity of both painful and non-painful sensations. Finally, it has been proposed that visceral hypersensitivity could explain the symptoms induced by nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) by interfering with gastric mechanosensory function1,3–10.

Gastric epithelial barrier dysfunction, low-grade inflammation, and leaky gut

Gastric epithelial barrier dysfunction in FD has been linked to low-grade inflammation and pyroptosis processes. The latter is an inflammatory form of cell death that occurs in response to microbial or damage signals and is mediated by the inflammasome and caspase-1. This phenomenon has been associated with loss of mucosal integrity, which leads to increased cell extrusion, allowing microbial translocation and subepithelial immune activation. In patients with FD, structural and functional abnormalities in the duodenal barrier have been identified. Loss of epithelial integrity and increased paracellular permeability are associated with symptoms such as epigastric pain, distension, and early satiety. The density of epithelial gaps, a marker of cell extrusion, has been validated as a reliable indicator of epithelial barrier disruption. Local immune activation involves mast cell and eosinophil activation, which, when located near nerve endings, could contribute to symptom generation. It has been proposed that certain patients are more susceptible to environmental or luminal factors, which trigger aberrant immune responses that impair cell junction proteins and facilitate the penetration of antigens and pathogens. Interleukins (IL), such as IL-5 and IL-13, promote eosinophil chemotaxis, perpetuating an inflammatory cycle that favors dysmotility and TH2 lymphocyte activation; this process may induce axonal necrosis and impaired gastrointestinal smooth muscle contractility, contributing to dyspeptic symptoms. Low-grade lymphoplasmacytic infiltration in the gastric mucosa of some patients has also been described. Collectively, these findings support the role of low-grade inflammation and epithelial dysfunction as key components in the pathophysiology of FD, especially in subgroups characterized by duodenal eosinophilia and compromised mucosal integrity. An impaired intestinal barrier allows the translocation of bacteria and microbial products to the subepithelial compartment, activating immune responses that may trigger neuroimmune inflammation and contribute to dyspeptic symptoms. In patients with FD, an increase in the density of epithelial gaps, a decrease in duodenal mucosal impedance, and alterations in the expression of tight junction proteins, such as zonulin, have been observed. Additionally, Paneth cell activation, defensin secretion, dysbiosis, and exposure to toxins or dietary components contribute to the deterioration of barrier function. These alterations facilitate the penetration of luminal antigens, which can activate mucosal immune cells and trigger low-grade inflammation, neuronal sensitization, and motor dysfunction. Furthermore, the paracellular pathway, regulated by tight junctions, may be affected by inflammatory mediators, such as tryptase and major basic protein, released by mast cells and eosinophils. These mediators increase permeability and perpetuate the vicious cycle of immune activation and barrier dysfunction. Current evidence indicates that increased intestinal permeability could be both a cause and a consequence of FD. However, whether it represents a primary phenomenon or an epiphenomenon derived from underlying inflammatory processes remains under debate.

Studies have shown that restoration of the epithelial barrier could alleviate symptoms, although clinical data in humans are limited and require further validation.

In conclusion, leaky gut represents an important component in the pathophysiology of FD in a subgroup of patients, associated with mild mucosal inflammation, dysbiosis, immune activation, and barrier dysfunction. Its more precise characterization will enable the development of personalized therapeutic strategies aimed at restoring intestinal mucosal integrity2,5,11–22.

Postinfectious functional dyspepsia

Postinfectious FD occurs following episodes of acute gastroenteritis and has been associated with an altered immune response, both local and systemic. The estimated prevalence of postinfectious FD is approximately 9.6% in adults, and the most frequently implicated etiological agents are Norovirus, Giardia lamblia, Salmonella spp., Escherichia coli O157, and Campylobacter spp. In contrast, Helicobacter pylori does not appear to be linked to postinfectious FD. Persistent changes in immune cells of the duodenal mucosa, such as macrophage activation and chemokine receptor 2, and the accumulation of eosinophils, suggest a prolonged inflammatory response. This may sensitize afferent nerve terminals through the release of mediators such as prostaglandins, contributing to the development of dyspeptic symptoms, particularly epigastric burning. During acute infection, an increase in the secretion of chemokines and inflammatory mediators, such as histamine and monocyte chemoattractant protein-1, is observed. These factors promote macrophage activation and the migration of immune cells toward the duodenal mucosa, perpetuating the low-grade inflammation that may persist even after resolution of the infectious process. These findings support the hypothesis that postinfectious FD results from an inability of the immune system to adequately resolve an initial infectious insult, leading to chronic immune activation in the mucosa and the development of persistent dyspeptic symptoms1,3,16.

Duodenal eosinophilia

Several studies have demonstrated an increase in eosinophils and activated mast cells in the duodenal mucosa of patients with FD, which has been correlated with impaired epithelial integrity, alterations in the expression of intercellular adhesion proteins, and structural and functional changes in the submucosal plexus. Mild inflammation of the duodenal mucosa, characterized by eosinophilic infiltration and increased epithelial permeability, has been identified in up to 40% of patients with FD. This infiltration is accompanied by an increase in the density of epithelial spaces, reflecting a significant alteration of the mucosal barrier. Furthermore, it has been shown that patients with FD and impaired duodenal integrity present more intense symptoms, such as early satiety, postprandial fullness, and abdominal pain. The interaction between eosinophils and mast cells plays a central role in the pathophysiology. Serotonin, released by mast cells, acts as a potent chemoattractant for eosinophils, which, upon degranulation, release proteins such as major basic protein that can increase smooth muscle reactivity and further activate mast cells and basophils. This synergy may explain part of the abdominal pain in patients without organic findings. Eosinophil granules contain cytotoxic mediators, such as cationic protein, eosinophil-derived neurotoxin, and peroxidase, which are toxic to the intestinal epithelium and contribute to dysmotility and impaired gastric relaxation. During their activation, these granules can be observed in the lamina propria, in association with nerve fibers of the duodenum, which reinforces the connection between low-grade inflammation and visceral sensitization. Microscopic duodenitis has been detected in more than 60% of biopsies from patients with FD, and its presence has been significantly linked to H. pylori infection; eosinophilic infiltration is more pronounced in patients positive for this bacterium. Additionally, concurrent systemic immune activation has been described; although eosinophils are a normal component of the intestinal lamina propria and participate in homeostatic immune functions, their excessive activation and degranulation promote tissue damage and epithelial remodeling. Three mechanisms of degranulation have been identified: exocytosis, cytolysis, and piecemeal degranulation. IL-5 and IL-13 amplify this inflammatory process, reinforcing their potential pathogenic role in FD2,5,12,16.

Influence of the central nervous system and the gut-brain axis

Functional dyspepsia has been frequently associated with psychological disorders such as anxiety and depression, which appear to influence symptom severity. Several studies have demonstrated a correlation between psychopathology questionnaire scores and the intensity of gastrointestinal distress.

Visceral hypersensitivity may arise not only from peripheral sensitization but also from alterations in the central processing of afferent visceral signals. Abnormal activity in brain regions involved in pain modulation, such as the anterior cingulate cortex, the insula, the thalamus, the prefrontal cortex, and the hippocampus, has been consistently reported in patients with FD. These areas are part of the visceral pain circuit.

During gastric distension, patients with FD show greater activation of the prefrontal cortex, the insula, the anterior cingulate cortex, and the thalamus compared to healthy controls. This cerebral hyperactivation could be due to the anticipation of visceral pain or to the memory of previous negative experiences. The increased response of the insula suggests a key role in altered interoceptive perception in these patients.

The gut-brain axis is implicated not only in sensory perception but also in autonomic and emotional modulation. It has been observed that anxiety can amplify brain activity in response to visceral stimuli, while depression is associated with dysfunction in the affective and cognitive processing of pain. These alterations could partially explain the gastrointestinal sensorimotor dysfunction observed in FD. Neuroimaging studies have demonstrated alterations in the functional and structural connectivity of the brain in patients with FD, including changes in regional cerebral metabolism and white matter. Inadequate deactivation of the amygdala and lack of activation of the pregenual cingulate cortex during visceral stimulation have been interpreted as a failure in the descending modulation of pain mediated by cognitive-affective processes. Furthermore, a biopsychosocial model has been proposed that integrates psychological factors with the pathophysiology of FD. Anxiety and depression could promote greater perception of physiological visceral signals, altering homeostatic and interoceptive processing. These alterations could be associated with hypermetabolism in regions such as the prefrontal cortex, insula, and anterior cingulate cortex, identified through cerebral glucose metabolism studies.

Collectively, FD could be considered a chronic functional pain syndrome characterized by altered central pain modulation and gut-brain axis dysfunction. These findings reinforce the importance of incorporating the assessment of psychological aspects in the diagnostic and therapeutic approach to patients with FD, including pharmacological or psychotherapeutic interventions targeting these processes1,11,15,17,18.

Role of gastric and intestinal microbiota in functional dyspepsia

Gastric and intestinal microbiota have emerged as a relevant component in the pathophysiology of FD. A specific dysbiosis has been observed in the duodenal mucosa of patients with FD, characterized by an increase in the relative abundance of Streptococcus and a decrease in anaerobic genera such as Prevotella, Veillonella, and Actinomyces. This alteration has been correlated with higher bacterial load and lower microbial diversity. The bacterial load of the duodenal mucosa has been negatively associated with quality of life, and its increase has been linked to greater severity of postprandial symptoms. Furthermore, an inverse relationship has been reported between the abundance of Streptococcus and anaerobic genera, suggesting an ecological imbalance that may contribute to low-grade inflammation and epithelial barrier dysfunction. Phylogenetically, an increase in Proteobacteria and a decrease in Actinobacteria, Bacteroidetes, and Firmicutes have been described in H. pylori-positive patients. These changes could influence motility and mucosal immunoreactivity, exacerbating dyspeptic symptomatology. On the other hand, certain bacterial taxa with possible causal associations with FD have been identified. The Clostridium innocuum group and the genus Ruminiclostridium 9 showed a positive correlation with the risk of FD, whereas the FCS020 group of the genus Lachnospiraceae was negatively associated. Lachnospiraceae, producers of short-chain fatty acids, could have a protective effect by promoting intestinal homeostasis and reducing duodenal permeability. Metabolites derived from the intestinal microbiota, such as secondary bile acids, short-chain fatty acids, and neurotransmitters, participate in gut-brain axis signaling and could modulate both digestive function and visceral perception. This interaction suggests that dysbiosis may not only be a consequence but also an active contributor to the pathogenesis of FD. Collectively, these findings support the potential role of gastric and intestinal microbiota as a key modulator of FD, opening the possibility for therapeutic strategies targeting the microbiome, including the use of probiotics, prebiotics, or specific dietary interventions2,15,19,20.

Conclusions

FD constitutes a complex and heterogeneous syndrome in which multiple pathophysiological mechanisms converge and interact dynamically to generate a broad spectrum of symptoms. The integrative analysis of available evidence confirms that there is no single pathological process capable of explaining all cases; rather, it is a multifactorial condition in which motor, sensory, immune, inflammatory, and microbial alterations combine variably depending on the patient.

Motility disturbances and visceral hypersensitivity represent central axes of the disease, affecting both gastric accommodation and emptying as well as the response to luminal chemical and mechanical stimuli. These changes do not occur in isolation but rather mutually potentiate with peripheral and central sensitization phenomena in close relationship with gut-brain axis activity and with emotional factors such as anxiety and depression, which can amplify symptom perception.

The integrity of the epithelial barrier emerges as another pathophysiological pillar. The increase in intestinal permeability, the activation of resident immune cells (eosinophils and mast cells), and low-grade inflammation generate a favorable environment for sensorimotor dysfunction. In this context, leaky gut should not be understood solely as a secondary finding, but rather as a phenomenon that can initiate or perpetuate the cascade of pathological events, particularly in subgroups with genetic predisposition or environmental susceptibility.

Post-infectious FD and duodenal eosinophilia illustrate how an initial insult can trigger a persistent inflammatory response, with epithelial remodeling, altered permeability, and sensitization of afferent pathways. These findings support the hypothesis that residual mucosal inflammation may constitute a prognostic marker and a relevant therapeutic target.

Furthermore, the characterization of the gastric and intestinal microbiota has revealed that dysbiosis could play a dual role both as a consequence and as a contributing factor to FD. The altered bacterial composition, decreased microbial diversity, and changes in bioactive metabolites suggest that microbiome modulation could become an emerging therapeutic approach, with potential to restore mucosal homeostasis and improve symptomatology.

Overall, FD should be understood as a syndrome of multiple interactions, in which motor and sensory dysfunctions, low-grade inflammation, dysbiosis, and alterations in central pain processing are intertwined. This integrative view reinforces the need for an individualized diagnostic and therapeutic approach that considers both peripheral and central mechanisms, as well as the psychosocial and environmental factors that influence clinical expression. The future management of FD is oriented toward personalized strategies, with therapies targeting well-characterized subphenotypes, combining pharmacological, dietary, microbiological, and psychological interventions. Only in this way will it be possible to advance toward effective and sustained symptom control, improving the quality of life of those suffering from this complex disorder.

Funding

The authors declare that they have not received funding for this study.

Conflicts of interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Ethical considerations

Protection of human and animal subjects. The authors declare that no experiments have been conducted on human subjects or animals for this research.

Confidentiality, informed consent, and ethical approval. The study does not involve patient personal data nor does it require ethical approval. The SAGER guidelines do not apply.

Statement on the use of artificial intelligence. The authors declare that they did not use any type of generative artificial intelligence for the writing of this manuscript.