Introduction

Functional dyspepsia (FD) and gastroparesis (Gp) represent a challenge for the gastroenterologist, as both are characterized by upper gastrointestinal symptoms such as epigastric pain, early satiety, and nausea; with the difference that FD is diagnosed by clinical criteria (after performing an upper gastrointestinal endoscopy), whereas Gp requires an objective measurement of gastric emptying (GE) time in the absence of mechanical obstruction1. The main objective of this review is to present the differences and similarities between FD and Gp, taking into account the available scientific evidence on the matter.

Gastroparesis and functional dyspepsia: establishing differences and similarities

Gp is a chronic condition (at least 3 months’ duration) whose most common symptom is nausea, which is present in 95% of cases, followed by vomiting2. Therefore, the predominance of nausea and vomiting over symptoms of epigastric pain and postprandial distress may be more indicative of a diagnosis of Gp than of FD. An observational study included 225 patients with delayed GE, of whom 54% had idiopathic Gp, 27% diabetic Gp, 11% atypical Gp, and 8% postsurgical Gp. These patients completed the PAGI-SYM (Patient Assessment of Upper Gastrointestinal Symptoms) questionnaire, which assesses the severity of gastrointestinal symptoms in Gp, FD, and gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD), and the R4DQ (Rome IV Diagnostic Questionnaire) to diagnose functional gastrointestinal disorders. On average, patients with Gp met the Rome IV criteria for two disorders of brain-gut interaction, the most frequent being FD in 90.8% and chronic nausea and vomiting syndrome in 83%. Regarding FD subtypes, postprandial distress syndrome was present in 88% and epigastric pain syndrome in 59.8%. No significant difference was found in GE scintigraphy, either by Gp etiology or by FD subtype3.

The diagnosis of Gp is frequently made erroneously, although it is now known that patients can fluctuate between Gp and FD over time. In a retrospective study conducted at the Mayo Clinic in Jacksonville from 2019 to 2021, 339 patients who were referred for Gp were evaluated, and their final diagnoses were analyzed. In 89% of cases, the most frequent symptom was nausea, followed by abdominal pain (76%), constipation (70%), vomiting (65%), subjective distension (37.5%), and early satiety (34%). The diagnosis of Gp was confirmed in only 19.5% of cases, while 80.5% received a different diagnosis, with FD being the most common alternative diagnosis (44.5%), followed by accelerated GE (12%), pelvic floor dysfunction (9.9%), constipation (8.4%), cannabinoid hyperemesis syndrome (7%) or drug-induced hyperemesis syndrome (5.1%), chronic nausea and vomiting syndrome (3%), median arcuate ligament syndrome (2.6%), and superior mesenteric artery syndrome (1%)4. This study highlights the importance of considering differential diagnoses when evaluating a patient with symptoms of gastric dysmotility.

Regarding risk factors for FD and Gp, there are some in common, such as postinfectious etiology. It is established that, following a gastrointestinal infection, the mean prevalence of postinfectious FD is 9.5%, with an odds ratio of 2.54 at more than 6 months after the event compared to a control group, with the most frequent etiological agents being Salmonella spp., Escherichia coli O157, Campylobacter jejuni, Giardia lamblia, and Norovirus5. In contrast, in postinfectious Gp the evidence is less robust and the data come from case series and retrospective studies. One aspect that has been demonstrated in this regard is that patients with postviral Gp tend to present gradual improvement of symptoms, require fewer hospitalizations, and maintain stable weight, compared to idiopathic cases, which present progressive symptoms and deterioration of quality of life6.

Unlike FD, in Gp there are secondary causes, such as pharmacological (opioids, glucagon-like peptide-1 receptor agonists), connective tissue diseases (systemic sclerosis, systemic lupus erythematosus), postsurgical (fundoplication, vagotomy, bariatric surgery), and neurological (Parkinson’s disease, dysautonomia)7.

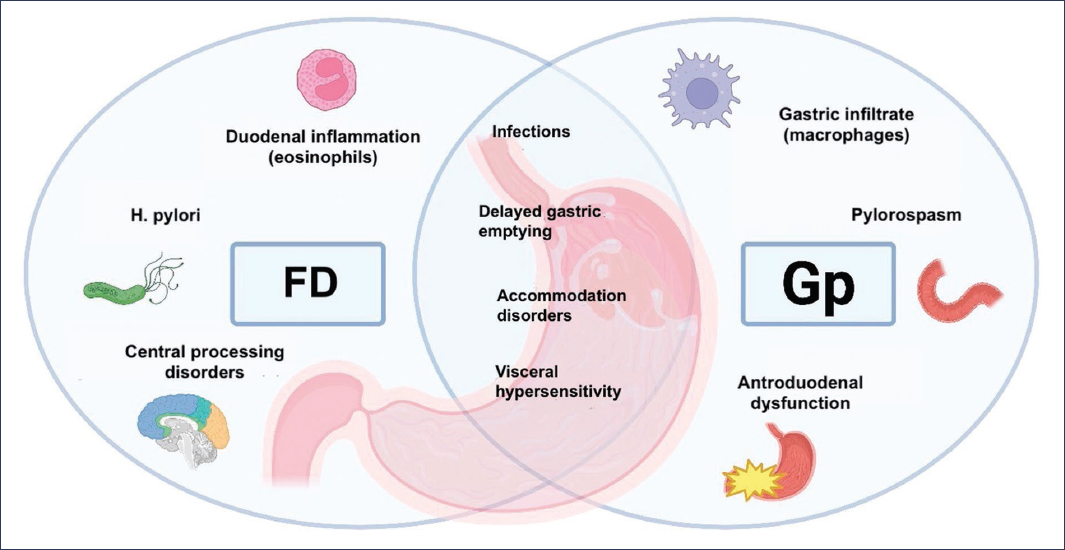

The pathophysiology of FD is complex and multifactorial, with notable alterations in gastric motility and accommodation, visceral hypersensitivity, dietary factors, and psychosocial aspects, all of which are also present in patients with Gp (Fig. 1). Indeed, if we consider that delayed GE is what distinguishes Gp from FD, it is noteworthy that up to 25-30% of patients with FD may present with it8.

Figure 1. Pathophysiological mechanisms of functional dyspepsia (FD) and gastroparesis (Gp). GE: gastric emptying.

Gastric emptying delay appears to be a dynamic process that can change over time; therefore, patients may transition from having Gp to FD during their clinical course, and vice versa. The Gastroparesis Clinical Research Consortium (GpCRC) published a study in 2021 that included 944 patients over a 12-year period, of whom 76% met criteria for Gp by scintigraphy, while 24% had normal gastric emptying and met criteria for FD. All patients presented similar clinical characteristics and severity of gastrointestinal symptoms. One year later, 42% of patients who initially had Gp were reclassified as FD according to the gastric emptying study results at that time; conversely, 37% of patients who initially had FD were reclassified as Gp. One of the authors’ explanations for this phenomenon is the lack of reproducibility of gastric emptying studies, due to intrinsic limitations in the test methodology and variations in its interpretation. It is also possible that, in certain patients, the gastric emptying rate fluctuates as the disease evolves. Changes in diagnosis were not associated with changes in symptom severity. An interesting finding was that both groups showed a loss of interstitial cells of Cajal and CD206+ macrophages compared to obese controls9.

An important concept is that GE is not associated with symptom severity or even with response to prokinetics, in either FD or Gp. This was demonstrated by Carbone et al.10 in a retrospective study of 504 patients, of whom 382 had normal GE and 122 had delayed GE (classified as idiopathic Gp). During a C13 breath test, six symptoms were assessed every 15 minutes: postprandial fullness, epigastric pain and burning, bloating, nausea, and belching. Of these, only nausea was significantly greater in patients with delayed GE (p = 0.01), with no correlation observed between the GE rate and the other symptoms. It is concluded that, in patients with FD and Gp, symptom severity does not correlate with the GE rate10.

It appears that other pathophysiological mechanisms, such as gastric accommodation and hypersensitivity to distension, correlate better with symptoms. Using a barostat and 3D ultrasound, patients with FD (n = 15) and healthy subjects (n = 15) were compared, and the relationship between gastric volumes and symptoms was evaluated. In the barostat test, patients with FD had lower postprandial volumes (200 ml of Nutridrink®) than healthy subjects (p = 0.001), in addition to presenting impaired proximal gastric accommodation. The 3D ultrasound results demonstrated a difference in the distribution of proximal and distal volume; in patients with FD, the proximal volume (fundus) was significantly lower and the distal volume (antrum) significantly higher, compared with healthy controls. This was associated with early satiety and postprandial fullness11.

This alteration in proximal gastric accommodation was also evaluated in patients with idiopathic Gp in whom barostat studies were performed. Of 58 patients with severe GE delay, 43% had impaired gastric accommodation, which correlated with a higher prevalence of early satiety (p < 0.005) and weight loss (p < 0.009). Hypersensitivity to gastric distension was associated with an increased prevalence of epigastric pain, early satiety, and weight loss. As in previous studies, the symptomatic pattern was not determined by the delay in GE12.

An additional mechanism involved in FD is the presence of eosinophils in the duodenum, especially in relation to postprandial distress syndrome. In a prospective study that included 22 patients with FD and 22 healthy controls, the number of eosinophils in the duodenal bulb (D1) and in the second portion of the duodenum (D2) was evaluated. The results showed an increase in the number of eosinophils in D2 in patients with postprandial distress symptoms13. In patients with Gp, there was an increase in the number of macrophages in the gastric body, which may correspond to an early stage of the pathophysiology.

In animal models, certain polymorphisms have been implicated in Gp, such as the polymorphism in the HMOX-1 gene, which encodes heme oxygenase and is expressed in activated macrophages (CD206+)14.

Similar to FD, patients with Gp typically present psychological alterations, which significantly influence the intensity of clinical symptoms. In a study conducted by Hasler et al.15, the Beck Depression Inventory (BDI) and State-Trait Anxiety Inventory (STAI) questionnaires were administered to a cohort of 299 patients with Gp. The results showed a positive correlation between symptom severity and the scores obtained on both instruments, indicating higher levels of anxiety and depression in the more severe cases. Furthermore, these elevated scores were associated with greater consumption of psychotropic medications, such as anxiolytics and antidepressants. Notably, these associations showed no relationship with the underlying etiology of Gp or with the degree of gastric retention observed15.

The treatment of FD and Gp is primarily aimed at symptomatic relief and improving the patient’s quality of life. In the case of FD, lifestyle modifications are recommended, including the elimination of alcohol and tobacco consumption, as well as the reduction of high-fat food intake. In patients with diabetic Gp, it has been observed that a diet composed of small particles may help reduce symptoms associated with delayed GE and gastroesophageal reflux. However, the available evidence on the efficacy of dietary interventions in these disorders is limited and of low methodological quality, which precludes establishing firm recommendations2,16.

Proton pump inhibitors have demonstrated efficacy in the symptomatic management of epigastric pain syndrome, achieving clinical improvement in approximately 34% of treated patients, compared with 25% in the placebo group, which translates to a number needed to treat estimated between 7 and 14. In the context of Gp, the use of proton pump inhibitors is only indicated in the presence of comorbidity with GERD, a condition reported in more than 50% of patients with Gp2,16.

Prokinetic agents are effective for symptoms associated with dysmotility in both FD and Gp. The term “prokinetic” refers to the improvement of motility and transit of gastrointestinal contents, primarily by amplifying and coordinating muscular contractions. These drugs exert their mechanism of action through a direct effect on the intestinal muscle or through activation of its excitatory innervation17.

In 2022, the GpCRC published a dynamic cohort study that evaluated the effects of domperidone on Gp symptoms. In the analyzed sample, 75% of participants had a diagnosis of Gp, and of these, 63% were idiopathic cases, while the remaining 25% manifested symptoms compatible with Gp but with GE within normal ranges. The study included a total of 748 patients, of whom 181 (24%) received treatment with domperidone at an average dose of 40 mg daily, and 567 comprised the group without domperidone. When comparing clinical outcomes between both groups, those who received domperidone showed statistically significant improvement in multiple aspects, such as total Gastroparesis Cardinal Symptom Index score (p = 0.003), nausea (p = 0.003), fullness (p = 0.005), upper abdominal pain (p = 0.04), GERD-associated score (p = 0.05), and overall quality of life (p = 0.05)18.

Prucalopride, a 5-HT4 agonist approved for the treatment of chronic constipation, was evaluated in a double-blind, crossover study in 34 patients with Gp (28 idiopathic, 7 men) who were randomized to receive prucalopride 2 mg four times daily or placebo for 4 weeks, followed by a 2-week washout period. Compared with placebo, prucalopride significantly improved the Gastroparesis Cardinal Symptom Index (1.65 ± 0.19 vs. 2.28 ± 0.20; p < 0.0001) and the subscales of satiety/fullness, nausea/vomiting, and bloating/distension19.

Velusetrag, another selective pan-gastrointestinal 5-HT4 agonist, is being studied in different gastrointestinal motility disorders. In a multicenter study in patients with Gp, treatment with velusetrag at a dose of 30 mg significantly increased the proportion of subjects with a ≥20% reduction in mean GE time, compared with placebo20.

In Gp, there are factors that predict the response to pharmacological treatment, with viral, idiopathic, and diabetic etiologies responding best to prokinetics. Conversely, in cases secondary to vagotomy or connective tissue disorders, and in diabetic patients with evidence of vagal neuropathy, the efficacy of prokinetics is usually suboptimal21.

Neuromodulators, particularly tricyclic antidepressants and selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors, modulate serotonin levels and therefore have an effect on motility and visceral nociception. They are recommended in both FD and Gp as second-line treatment4,22. The efficacy of mirtazapine, at a dose of 15 mg daily, was evaluated in patients with Gp and poor symptom control. During a 4-week follow-up period, statistically significant improvements were observed in several cardinal symptoms of the disease, including nausea, vomiting, retching, and the perception of loss of appetite, at both 2 and 4 weeks of treatment23. In FD, mirtazapine is recommended primarily in patients with postprandial distress accompanied by weight loss16,22.

Endoscopic interventions, indicated only in Gp and not in FD, include intrapyloric injection of botulinum toxin, which has demonstrated short-term symptom improvement (< 6 months), with no impact on the GE rate24. Gastric peroral endoscopic pyloromyotomy has a clinical success rate at 12 months of 56%, with moderate effectiveness in the treatment of Gp; therefore, it should be considered in selected cases with more severe symptoms and in those patients who respond to botulinum toxin injection25,26. Finally, gastric electrical stimulation, using the Enterra® system, is approved by the Food and Drug Administration of the United States of America under the humanitarian use device category. This classification applies to technologies intended for the treatment of conditions affecting fewer than 8,000 people per year in that country. The available evidence suggests that this therapeutic approach may induce improvement in specific symptoms, such as nausea, vomiting, and loss of appetite, in patients with refractory Gp. However, studies conducted to date have not shown a significant impact on more global parameters such as quality of life, nutritional status, or GE rate21.

Conclusions

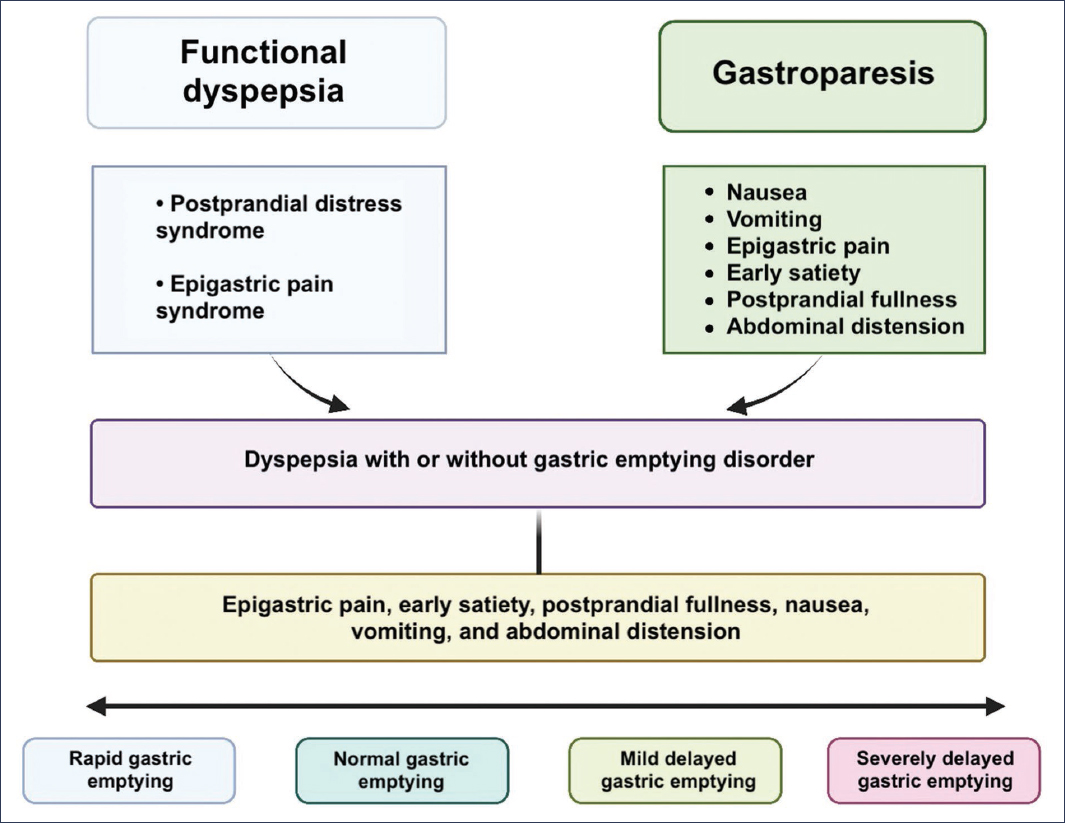

Both FD and Gp constitute the two gastric sensorimotor disorders that occur most frequently in clinical practice, and their diagnosis and treatment represent a challenge. By definition, they appear to be different conditions, but throughout this review we have seen how they share symptoms, etiology, pathophysiological mechanisms, and overlapping treatments. Lacy et al.27 propose defining these patients as FD with or without delayed GE (Fig. 2). For this reason, the GpCRC considers that these pathologies are part of the same spectrum of gastroduodenal sensorimotor dysfunction, in which FD is found at the milder end and refractory Gp is at the more severe end.

Figure 2. Spectrum of gastroduodenal sensorimotor disorders. GE: gastric emptying.

Funding

The authors declare that they have not received funding for this study.

Conflicts of interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Ethical considerations

Protection of human and animal subjects. The authors declare that no experiments were performed on human subjects or animals for this research.

Confidentiality, informed consent, and ethical approval. The study does not involve patient personal data nor does it require ethical approval. SAGER guidelines do not apply.

Declaration on the use of artificial intelligence. The authors declare that they did not use any type of generative artificial intelligence for the writing of this manuscript.