Introduction

Functional dyspepsia (FD) is one of the most common disorders of gut-brain interaction, characterized by persistent symptoms such as postprandial fullness, early satiety, epigastric pain, and burning, in the absence of demonstrable structural lesions. Beyond its high prevalence, FD represents a clinical challenge due to its chronic course, its negative impact on quality of life, and its complex pathophysiology, in which motor, sensory, immune, and psychological alterations converge.

The growing evidence regarding the bidirectionality of the gut-brain axis has highlighted the role of psychosocial factors, such as chronic stress, anxiety, depression, and somatoform disorders, in the genesis and perpetuation of FD. In turn, FD may be a predisposing factor or amplifier of affective symptoms, consolidating a clinical cycle that is difficult to break. Given this complexity, new therapeutic strategies have emerged, including structured psychological interventions and modulation of the gut-brain axis through psychobiotics.

Association of functional dyspepsia with anxiety, depression, and somatoform disorders

Globally, it is estimated that between 30% and 60% of patients with FD present comorbidity with anxiety or depression1,2, and up to 50% with somatoform disorders, such as somatization disorder3.

In Sweden, a population-based study reported a prevalence of FD of 15.6% at baseline and 13.3% at 10 years of follow-up. Anxiety was associated with FD (odds ratio [OR]: 6.30; 99% confidence interval [CI]: 1.64-24.16) and with the postprandial distress subtype both at baseline (OR: 4.83; 99% CI: 1.24-18.76) and at follow-up (OR: 8.12; 99% CI: 2.13-30.85). The presence of anxiety at baseline was associated with the development of new cases of FD at follow-up (OR: 7.61; 99% CI: 1.21-47.73)4. In Latin America, epidemiological studies are limited, but a high prevalence of anxious and depressive symptoms has been reported in patients with functional gastrointestinal disorders.

Historically, gastroparesis and FD have been classified as distinct gastrointestinal disorders, differentiated by the presence or absence of delayed gastric emptying, respectively. In a systematic review with meta-analysis, the overall prevalence of anxiety was similar (p = 0.12) in patients with gastroparesis (49%) and FD (29%), as was the prevalence of depression in patients with gastroparesis (39%) and FD (32%) (p = 0.37). The relationship between anxiety (r = 0.30) and depression (r = 0.32) was observed only in patients with FD5.

Patients with FD may manifest alterations in gastric accommodation and emptying, as well as visceral hypersensitivity. In a study of 259 consecutive patients with FD according to Rome II criteria who underwent gastric barostat testing, breath testing, and psychiatric questionnaires (including the State-Trait Anxiety Inventory), those with a comorbid anxiety disorder exhibited significantly slower initial increases in gastric volume, reached a lower maximum, and showed a slower return to baseline level compared to patients without an anxiety disorder6.

Somatization disorder, also known as somatic symptom disorder, is defined as the presence of multiple persistent physical symptoms that cannot be fully explained by a general medical condition and that are associated with excessive thoughts, feelings, and behaviors related to those symptoms, causing significant distress and negatively affecting daily life7.

Somatization, understood as the tendency to experience and communicate psychological distress through physical symptoms, also contributes significantly to the symptom burden in FD, often mediating the effects of depression on symptom severity1.

Somatization frequently acts as a psychopathological bridge between anxiety/depression and functional disability. Somatic symptoms have been found to mediate the bidirectional relationship between affective symptoms and functional dysfunction, contributing to chronification and excessive demand for medical care8.

Somatic symptoms are not merely innocent byproducts of anxiety and depression; they are true “control centers” that can amplify and maintain emotional distress through mediation (Table 1).

Table 1. Why does mediation occur in somatization?

| Step | Proposed Mechanism | Description of the mechanism | Practical indicator |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Hyperarousal (locus coeruleus) | Autonomic storm with cardiorespiratory sensations | Palpitations, shortness of breath, BAI/PHQ-15 |

| 2 | Negative interoceptive inference | Catastrophic predictive interpretation with pessimistic rumination (depressive cognition) | Health anxiety, catastrophizing, B-IPQ |

| 3 | Behavioral suppression/withdrawal | Maintains anxiety triggers untested (without disconfirmation) | Anergy on PHQ-9; reduced physical activity (steps) |

| 4 | Vicious cycle | Bodily distress with interpretation as threat and bodily anxiety | Increasing use of the healthcare system with multiple consultations. |

|

B-IPQ: Brief Illness Perception Questionnaire; BAI: Beck Anxiety Inventory; PHQ: Patient Health Questionnaire. |

|||

The integrated biopsychosocial approach is key in the care of patients with FD and psychiatric comorbidity. The Asociación Mexicana de Gastroenterología and the Asociación Mexicana de Neurogastroenterología y Motilidadpropose the following good clinical practice recommendations9:

- − Manage patients with disorders of gut-brain interaction and psychiatric comorbidity in conjunction with psychiatry when combination neuromodulator therapy or psychotherapy is required.

- − Screen for depression and anxiety in all patients with disorders of gut-brain interaction, using self-administered scales (Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale [HADS], Patient Health Questionnaire-9 [PHQ-9], or Generalized Anxiety Disorder 7-item [GAD-7]).

- − Consult with a mental health provider (psychiatry or psychology) for patients with disorders of gut-brain interaction who present with moderate to severe depression or anxiety, use of neuromodulators at doses with central action, or eating disorders.

- − Multidisciplinary management of disorders of gut-brain interaction associated with affective and somatic disorders.

- − Adopt a more comprehensive, patient-centered approach, considering both physical symptoms and psychological and behavioral aspects, and identify severity predictors such as alexithymia, persistent somatization, and demoralization.

- − Use validated and accessible assessment tools (PHQ-15 and Symptom Checklist-90 [SCL-90]) in patients with somatic symptom disorders.

Role of stress and central sensitization

Accumulated evidence from animal models, functional neuroimaging studies, and clinical cohorts points toward a complex interaction of the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis, the autonomic response, neurogenic inflammation, and sensorimotor dysfunction of the upper digestive tract.

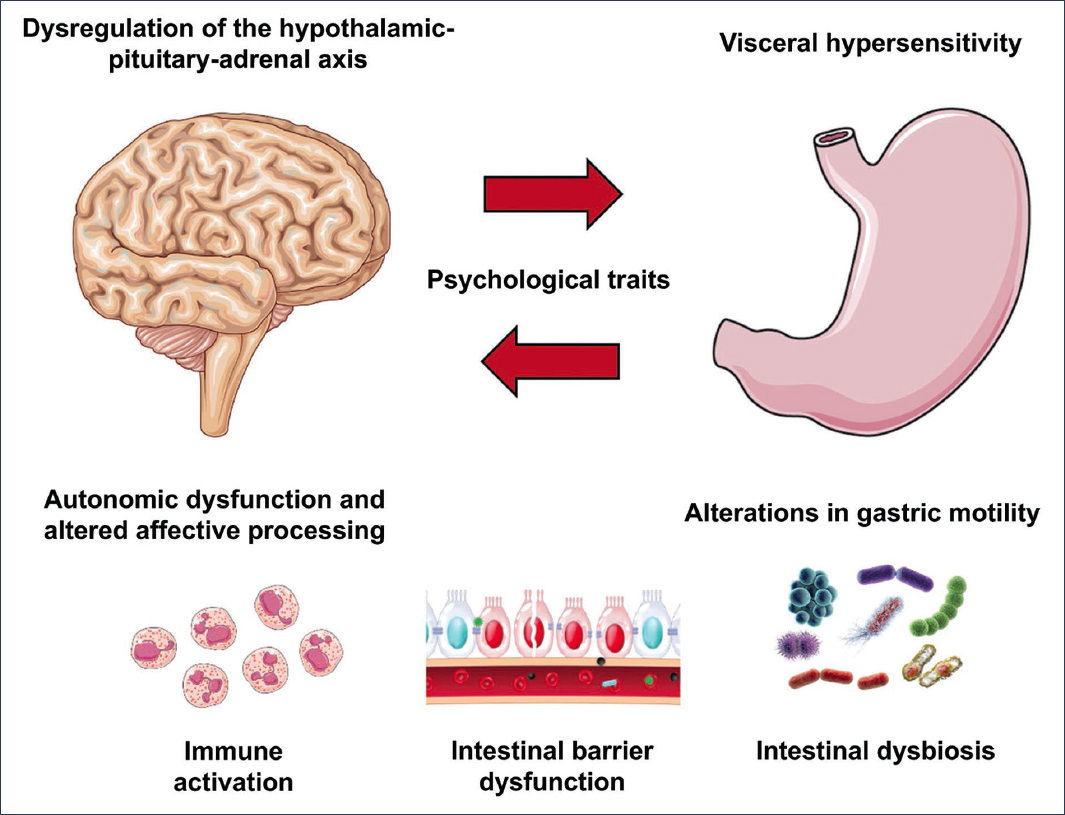

The pathophysiological mechanisms underlying FD, anxiety, depression, and somatoform disorders are complex and multidirectional (Fig. 1). Stress and central hypersensitivity play significant roles in the pathophysiology of FD, especially when considering the influence of anxiety, somatization, and other psychological factors on symptom severity. Chronic stress is known to exacerbate FD symptoms by inducing hypersensitivity in gastric vagal afferents, which are fundamental for detecting mechanical stimulation related to food intake and modulating gastrointestinal function10.

Figure 1. Bidirectional pathophysiological mechanisms. Dysregulation of the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis leads to an altered stress response. Autonomic dysfunction and impaired affective processing occur primarily in the insula and cingulate cortex. Visceral hypersensitivity is mediated by central and peripheral mechanisms. Gastric motility is characterized by delayed emptying and impaired fundic accommodation. The most frequent psychological traits are alexithymia, neuroticism, and dysfunctional coping styles. Immune activation by eosinophils and mast cells in the duodenal mucosa correlates with symptoms. Intestinal barrier dysfunction increases intestinal permeability through reduction of zonulin-1. Duodenal intestinal dysbiosis is associated with postprandial symptoms1,3,6,8,11,30.

Psychosocial stress, particularly when chronic or associated with early adverse experiences, acts as a predisposing, triggering, and perpetuating factor for FD. Population-based studies have shown that patients with FD exhibit a higher frequency of stressful events prior to symptom onset and a greater prevalence of affective disorders such as anxiety and depression, which reinforces the bidirectionality of the gut-brain relationship1.

Central hypersensitivity, an enhanced response of the central nervous system to normal sensory stimuli, is influenced by psychological factors such as anxiety and somatization. In particular, anxiety has been associated with increased gastric sensitivity and greater symptom severity1,11.

Rodent models have demonstrated that chronic mild unpredictable stress induces anxiety- and depressive-like behaviors, weight loss, and decreased food intake. These changes are accompanied by hypersensitivity of gastric vagal afferents responsible for transmitting mechanical information to the brain, which results in increased perception of distension and fullness10.

Psychosocial factors, including perceived stress, and psychiatric disorders can alter gut-brain signaling, leading to motility disorders and visceral hypersensitivity. The interaction between stress and central hypersensitivity is supported by evidence showing that stress can modulate the expression of inflammatory cytokines and neuropeptides, such as corticotropin-releasing factor, which are implicated in stress-induced gastric hyperalgesia12.

Visceral hypersensitivity is one of the most frequently documented mechanisms in patients with FD. It is estimated that between 34% and 66% have an increased perception of gastric distension, which is associated with postprandial pain, early satiety, and nausea1,10. This hypersensitivity may result from both peripheral sensitization (vagal and spinal afferents) and central facilitation. At the central level, functional magnetic resonance imaging studies have demonstrated increased activation in regions such as the insula, thalamus, and anterior cingulate in response to gastric distension, suggesting dysfunction in interoceptive processing and pain modulation circuits1. Additionally, reduced descending functional connectivity has been implicated in the lack of visceral pain inhibition.

Psychological therapies in functional dyspepsia

The multifactorial pathophysiology of FD and the limited efficacy of pharmacological treatments have motivated the development of complementary strategies focused on the modulation of visceral perception and cognitive-affective processes. Psychological therapies have proven to be effective in the treatment of FD, particularly in contexts of associated anxiety, depression, or somatoform disorders. These therapies are an integral part of the biopsychosocial approach recommended for the management of FD, which emphasizes attention to both the psychological and physiological components of the disorder, and should be considered from early stages of treatment rather than as a final option.

Cognitive-behavioral therapy

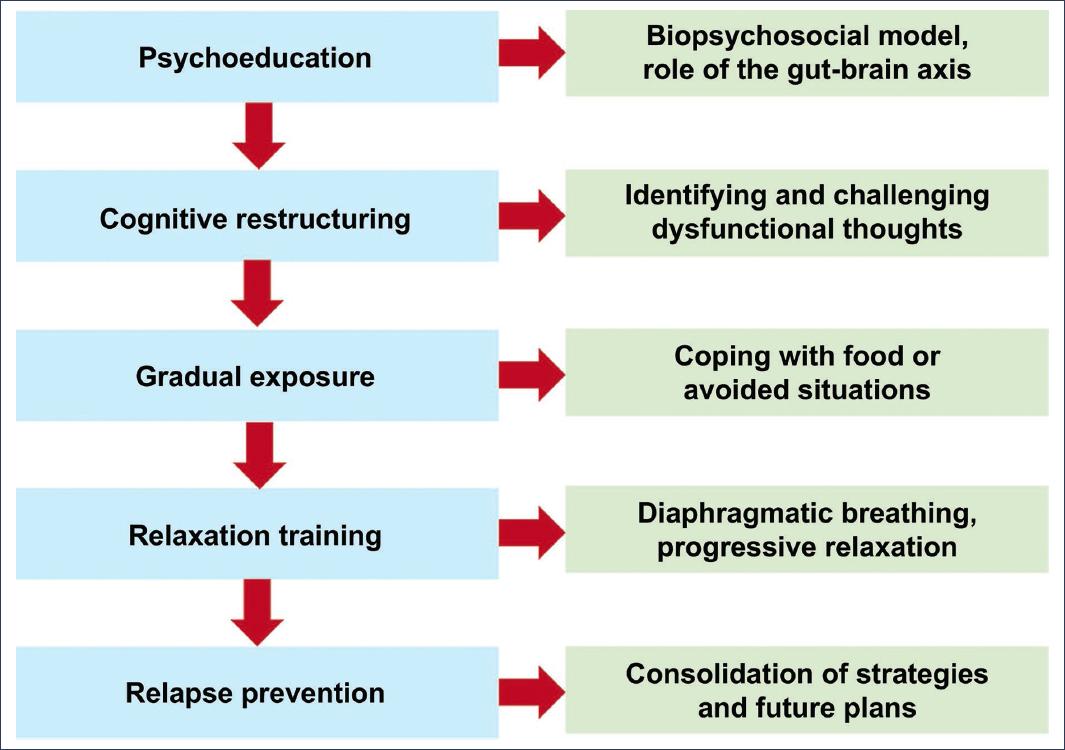

Cognitive-behavioral therapy (CBT) is the psychological intervention with the strongest empirical support in the treatment of functional gastrointestinal disorders. It is based on identifying and modifying dysfunctional thought patterns, irrational beliefs, and avoidance behaviors that amplify symptoms (Fig. 2).

Figure 2. Typical components of a cognitive-behavioral therapy protocol for functional dyspepsia15.

A clinical trial (n = 49) randomized 24 participants to the core conflictual relationship theme method and 25 to standard medical treatment, and at 12 months of follow-up, significant improvement was observed in all FD symptoms (heartburn/regurgitation, nausea/vomiting, satiety, fullness, and abdominal pain)13.

A meta-analysis of 14 randomized studies (n = 1,434) demonstrated that psychological interventions, particularly CBT, significantly improve dyspeptic symptoms (standardized mean difference [SMD]: −1.06) and reduce anxiety (SMD: −0.80) and depression (SMD: −1.11), with sustained effects for up to 12 months14. Individual or group CBT improves quality of life, decreases the frequency and intensity of symptoms, and optimizes psychosocial functioning15. Brief or short-duration CBT has not shown significant differences compared to active controls, which highlights the importance of the format and duration of the intervention.

Despite limited data, the available evidence suggests that psychological therapy is beneficial in the treatment of patients with FD, and should be considered by treating physicians if it is available and patients are willing.

Hypnotherapy

Ericksonian hypnotherapy, developed by Milton H. Erickson, is characterized by the use of techniques such as distraction, fractionation, progression, suggestion, reorientation, and utilization. These strategies promote solution-focused therapy and empower the patient, facilitating cognitive and behavioral changes. Although the scientific evidence regarding its efficacy remains limited and occasionally questioned, some studies suggest that it may contribute to cognitive restructuring and symptom reduction in certain disorders. For example, it has been used in the treatment of eating disorders, phobias, and obsessive behaviors16. In clinical practice, a total of 13 sessions of 45-50 minutes are conducted, focused on clear and specific objectives defined by the patient17.

Gut-brain axis-focused hypnotherapy uses guided suggestions and visualization to modulate visceral perception and reduce anticipatory anxiety. It has been proposed that 12 weekly hypnotherapy sessions significantly improve dyspeptic symptoms and emotional distress, with benefits maintained at 12 months18.

Hypnotherapy has been particularly effective in patients with epigastric pain syndrome-type functional dyspepsia and with a visceral hypersensitivity profile. Its application is supported by clinical guidelines and is recommended as part of brain-gut therapies for refractory chronic pain15. Its limitations include limited availability of trained therapists, cultural stigmas, and lack of protocol standardization, although group or virtual formats have shown promise.

Mindfulness

Mindfulness-based therapies, such as the mindfulness technique, integrate principles of CBT with meditative practices oriented toward the acceptance of internal experience without judgment, and have also shown promise in the management of FD. As a technique, mindfulness enables emotional regulation, relaxation, and progressive desensitization to triggering stimuli19.

An 8-week randomized pilot trial (n = 28) reported a 90% improvement in symptoms in the mindfulness group, compared to 45% in the standard treatment group (p = 0.063)20. In a randomized study (n = 80), patients in the mindfulness group reported lower gastrointestinal symptom scores and better quality of life at 8 weeks compared to the standard treatment group (p < 0.05)21. In both studies, acceptability and adherence were good, and they were conducted in settings with high patient turnover.

Mindfulness-based approaches help reduce visceral hypersensitivity and improve cognitive appraisal of symptoms, thereby contributing to better quality of life.

Modulation of the gut-brain axis with psychobiotics

There is increasing evidence, particularly from animal research, indicating that the gut microbiome significantly influences brain function.

In humans, studies have revealed links between the composition and activity of the microbiome with emotional and behavioral disorders, in addition to showing correlations with certain patterns observed in brain neuroimaging studies. Dysbiosis has been identified in patients with FD, characterized by an increase in Streptococcus in the oral cavity, stomach, and duodenum22.

Probiotics are live microorganisms that, when administered in adequate amounts, confer a health benefit to the host23. Psychobiotics are a subgroup of specific probiotics with behavioral and cognitive properties in the brain-gut axis, capable of modulating neurotransmitter levels, reducing inflammation, and improving intestinal barrier function24,25.

Lactobacillus plantarum strengthens the intestinal barrier through the production of capsular polysaccharides that reinforce tight junctions between enterocytes (such as ZO-1) and occludin. Furthermore, the L. plantarum PS128 strain has demonstrated psychotropic properties in animal models and has been observed to decrease cortisol levels and increase the concentration of neurotransmitters, such as dopamine and serotonin, in key brain regions including the prefrontal cortex and the striatum26,27.

A decrease in the production of proinflammatory cytokines, such as tumor necrosis factor-alpha and interleukins 6 and 1, has been demonstrated, while levels of anti-inflammatory cytokines, such as interleukin-10, increase. They also modulate neurotrophic factors, such as brain-derived neurotrophic factor and glial-derived neurotrophic factor, which are involved in neuronal plasticity and the stress response22.

The use of Bifidobacterium animalis subsp. lactis BL-99 has been shown to significantly improve FD symptoms, including postprandial fullness, early satiety, and epigastric pain, with dose-dependent effects28. Positive changes in the intestinal microbiota were also observed, with an increase in Faecalibacterium prausnitzii and Bacteroides ovatus, bacteria associated with the production of short-chain fatty acids beneficial for intestinal mucosal integrity.

The use of psychobiotics in FD is promising, as they may alleviate both gastrointestinal and psychological symptoms by remodeling the microbiota-gut-brain axis (Table 2).

Table 2. Psychobiotics with relevant experimental or clinical evidence22,26–29

| Strain | Observed effects |

|---|---|

| Bifidobacterium longum 1714 | Reduction of stress reactivity |

| Lactobacillus plantarum PS128 | They increase dopamine and serotonin, decrease anxiety and depression |

| Bifidobacterium animalis subsp. lactis BL-99 | Reduces dyspeptic symptoms, gastrointestinal modulation |

| Fructooligosaccharides/galactooligosaccharides (prebiotics) | Increases brain-derived neurotrophic factor, decreases inflammation, improves mood |

Conclusions

The current understanding of FD has evolved toward an integrative model that recognizes the involvement of psychological, immunoneuroendocrine, and microbial factors. Mechanisms such as visceral hypersensitivity, hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis dysfunction, and neuroinflammation explain why symptoms such as anxiety, depression, and somatization are more than comorbidities and act as clinical amplifiers. This understanding has driven broader therapeutic strategies, including structured psychotherapies (such as CBT, hypnotherapy, and mindfulness), which have demonstrated sustained efficacy. In parallel, modulation of the gut-brain axis through psychobiotics, with strains such as L. plantarum PS128 and B. animalis BL-99, represents an emerging approach with dual clinical potential for digestive and affective symptoms. The treatment of FD should be oriented toward a personalized and multidisciplinary model, incorporating patient-centered interventions supported by evidence, which integrate psychotherapeutic tools, neuromodulation, and microbiome-targeted strategies.

Funding

The author declares that no funding was received for this study.

Conflicts of interest

The author declares no conflicts of interest.

Ethical considerations

Protection of human and animal subjects. The author declares that no experiments have been conducted on human subjects or animals for this research.

Confidentiality, informed consent, and ethical approval. The study does not involve personal patient data nor does it require ethical approval. The SAGER guidelines do not apply.

Declaration on the use of artificial intelligence. The author declares that artificial intelligence (ChatGPT and Open Evidence) was used for the literature review, writing, and editing of this article.