Introduction

Eating disorders (EDs) constitute a group of chronic disorders characterized by eating patterns that negatively affect the biopsychosocial health of patients, with a high potential for disability and risk of mortality1,2. EDs share pathophysiological mechanisms with disorders of gut-brain interaction (DGBI), such as alterations in central processing and abnormal activity patterns in specific brain regions3,4. These disorders often present in an overlapping manner, and one of the DGBI most strongly associated with EDs is functional dyspepsia (FD)5,6. The identification of this overlap syndrome represents a diagnostic and therapeutic challenge, as many of the manifestations of EDs can be confused with the symptomatology of FD, especially with the postprandial distress syndrome (PDS) spectrum. In turn, FD symptoms may act as a cause or triggering factor for some EDs2,7–9. The clinical and pathophysiological association between FD and EDs depends on the ED subtype, which currently includes six subtypes according to the 5th edition of the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM-5)10,11 (Table 1).

Table 1. Comparison of the main clinical, epidemiological, and diagnostic characteristics among the three phenotypes of avoidant/restrictive food intake disorder, postprandial distress syndrome with early satiety, anorexia nervosa, bulimia nervosa, and cibophobia

| Disorder – phenotype | Characteristics | Symptoms or findings | Affected group | Association with weight loss | Diagnostic criteria |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ARFID – phenotype 1 (selective) | Intake limited to certain types of foods (e.g., texture, odor) | Reduced intake due to sensory impairment | Children, ASD | Yes | DSM-5: ARFID |

| ARFID – phenotype 2 (limited intake) | Loss of interest or appetite | Low intake across all meals, without discrimination | Children, ASD | Yes | DSM-5: ARFID |

| ARFID – phenotype 3 (aversive) | Fear of physical consequences of eating | Avoidance due to anxiety or postprandial symptoms | DGBI, digestive pathology | Yes | DSM-5: ARFID |

| Postprandial distress syndrome | Early satiety and postprandial discomfort | Rapid filling, persistent fullness | Women, functional dyspepsia | Yes | Rome IV |

| Anorexia nervosa | Severe restriction with weight concern | Weight loss, body image distortion | Young women | Yes | DSM-5: anorexia |

| Bulimia nervosa | Binge eating and compensatory behaviors | Episodes with guilt or shame | Young women | Variable | DSM-5: bulimia |

| Cibophobia | Irrational fear of certain foods or of eating | Extreme anxiety related to food | ASD, psychiatric disorders | No, in general | It is not a formal diagnosis (it may fall under anxiety or specific phobia) |

|

ARFID: avoidant/restrictive food intake disorder; ASD: autism spectrum disorder; GDBI: disorders of gut-brain interaction. |

|||||

Prevalence of functional dyspepsia in patients with anorexia nervosa, bulimia nervosa, and binge eating disorder

Gastrointestinal symptomatology in patients with eating disorders is frequent, with a reported prevalence of 72%. Among these symptoms, dyspeptic symptoms within the postprandial distress syndrome spectrum are the most common, particularly postprandial fullness and early satiety, with prevalences of 47% and 39%, respectively. Epigastric pain is less frequent but occurs in 27% of cases12.

The prevalence of FD varies according to the type of ED, reaching up to 83.3% in bulimia nervosa and 90% in anorexia nervosa13. In other disorders, such as avoidant/restrictive food intake disorder (ARFID), binge eating disorder, and rumination syndrome, the prevalence is lower, with values of 66.7%, 53.6%, and 18.9%, respectively7,14,15 (Table 1). Regarding pica, no specific prevalence of FD has been described, and the relationship between both is difficult to establish due to the association of pica with iron deficiency anemia, a frequent complication of various gastrointestinal pathologies, such as erosive gastropathy, atrophic gastritis, Helicobacter pylori infection, peptic ulcer, and enteropathies, which may manifest with dyspeptic symptoms16.

Bidirectional relationship between eating disorders and functional dyspepsia

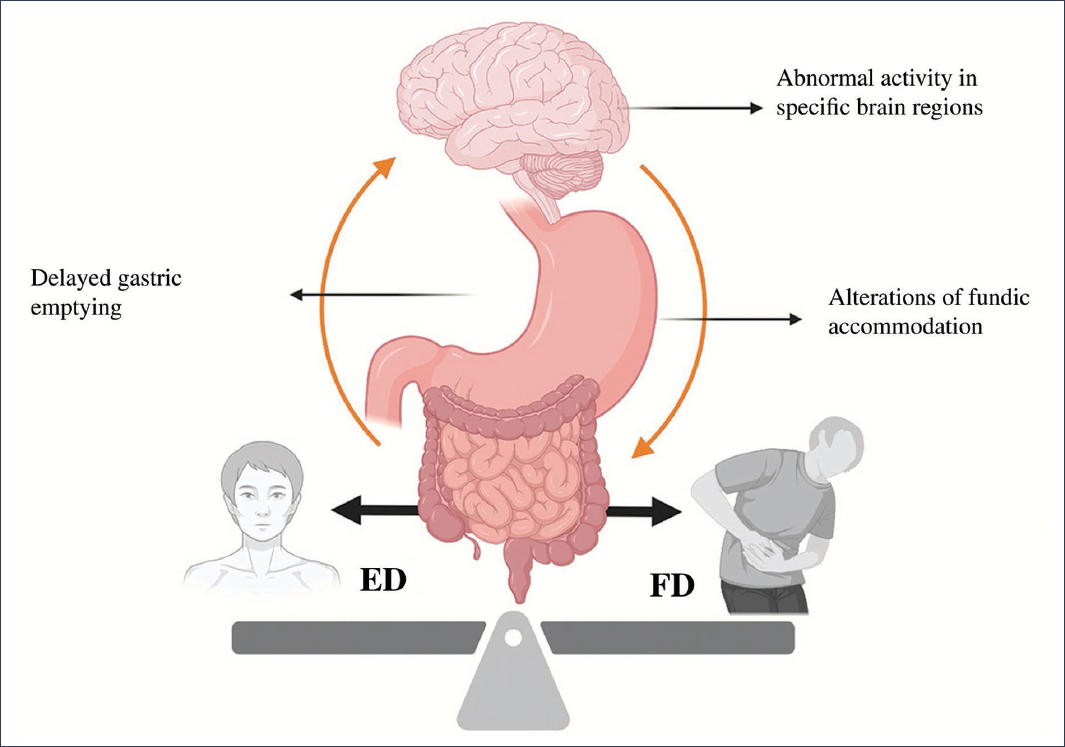

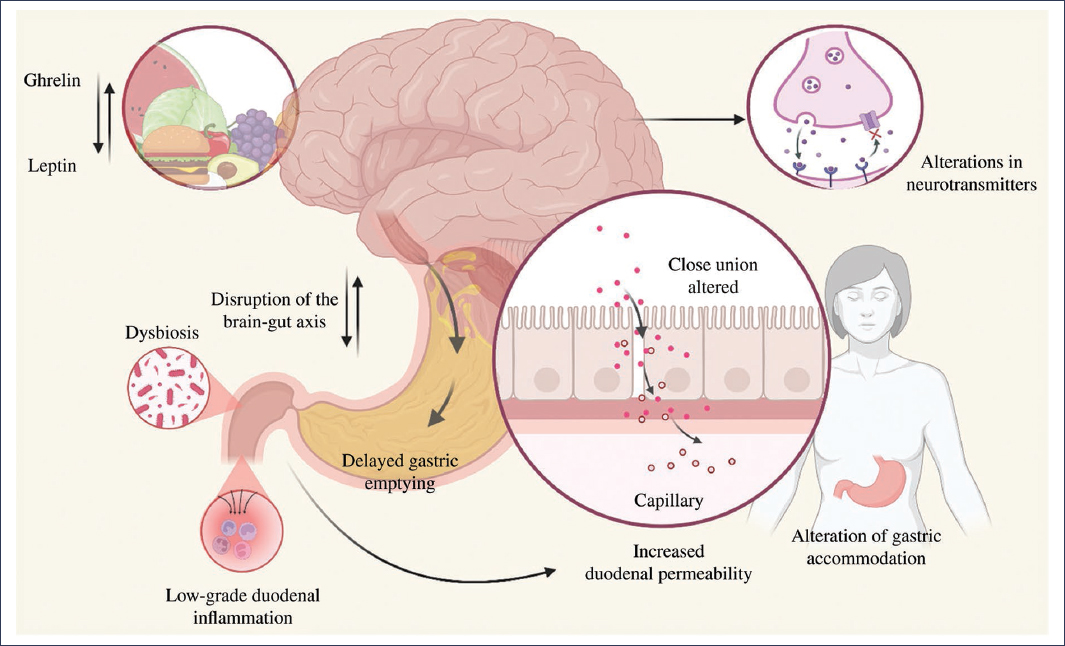

Eating disorders share established pathophysiological mechanisms with FD, such as abnormal activity patterns in specific brain regions, delayed gastric emptying, and alterations in fundic accommodation3,4,14,17 (Fig. 1). Similarly, they also share proposed pathophysiological mechanisms in FD, such as low-grade duodenal inflammation, dysbiosis, and alterations in the ghrelin-leptin interaction9,18–25 (Fig. 2). By sharing pathophysiological mechanisms, this could explain the association and high prevalence of FD and certain eating disorders; however, it could also be explained by a clinical context in which FD symptoms might be secondary to eating disorders, or be confused with primary symptoms of these disorders (e.g., postprandial fullness secondary to binge eating episodes or confusion of ARFID with early satiety)7,14.

Figure 1. Shared mechanisms in the pathophysiology of eating disorders (ED) and functional dyspepsia (FD) (created with BioRender, 2025).

Figure 2. Proposed pathophysiological mechanisms in functional dyspepsia, including alterations in specific neuroanatomical sites, neurotransmitter irregularities, increased intestinal sensitivity, impaired fundic accommodation, low-grade duodenal inflammation (which leads to increased duodenal permeability), and dysbiosis (created with BioRender, 2025).

Risk Factors

Anxiety is considered an independent risk factor for FD and EDs. In a cohort study conducted by Aro et al.26, it was reported that anxiety is an independent risk factor for developing FD over a 10-year follow-up (odds ratio [OR]: 7.61; 99% confidence interval [CI]: 1.21-47.73), particularly in patients with PDS (OR: 4.83; 99% CI: 1.24-18.76)26. Similar to anxiety, but to a lesser extent, depression is a factor associated with FD, with a reported prevalence of 20.9% in patients with FD and 63.3% in those with refractory FD27.

Anxiety disorder and depression are also independent risk factors for the development of EDs. This was demonstrated by Trompeter et al.28 in a meta-analysis of prospective studies, in which a longitudinal association between anxiety and EDs was identified (OR: 1.58; 95% CI: 1.21-2.07, p = 0.002). Likewise, a relationship between depressive disorder and EDs has been evidenced (OR: 1.82; 95% CI: 1.60-2.08; p < 0.0001)28,29.

Dysbiosis appears to be an independent risk factor for the development of FD, as has been proposed in postinfectious FD, and is suggested as a possible mechanism in EDs20,22,30. In patients with FD, an increase in the abundance of the phylum Fusobacteria and the genera Alloprevotella, Corynebacterium, Peptostreptococcus, Staphylococcus, Clostridium, and Streptococcus has been found, as well as a decrease in the genera Actinomyces, Gemella, Haemophilus, Megasphaera, Mogibacterium, and Selenomonas31. In addition to these findings, a negative symptomatic correlation has been identified between the abundance of Streptococcus and Prevotella with FD symptomatology, and a clinical response to rifaximin in specific FD groups has also been described31,32.

Similar to depression, but with less evidence, alterations in the gut microbiota have been found in the population with eating disorders, especially in the group with binge eating disorder. In these patients, a decrease in Akkermansia and Intestinimonas has been observed, as well as an increase in the density of Bifidobacterium, Roseburia, and Anaerostipes33.

Clinical presentation of eating disorders: a gastroenterological approach

The symptomatology of FD and EDs may be confused due to inadequate interpretation by the physician or imprecise expression by the patient, given the subjective nature of the symptoms. The use of pictograms to objectively exemplify the symptomatology could be useful in clinical practice by increasing the diagnostic yield of FD and discriminating those cases with distinct symptomatology34.

Among the symptoms that may generate confusion are early satiety, which may be confused with cibophobia or with limited intake in ARFID, as well as vomiting associated with FD, which may be confused with rumination, bulimia nervosa, or anorexia nervosa34–36.

In the clinical approach, it should also be considered that dyspeptic symptoms may be secondary to an ED (e.g., postprandial fullness secondary to binge eating disorder)7. Similarly, EDs may develop as a consequence of FD symptomatology, as in the case of the aversive phenotype of ARFID secondary to epigastric pain, epigastric burning, or postprandial fullness2,36–39.

Diagnostic tools

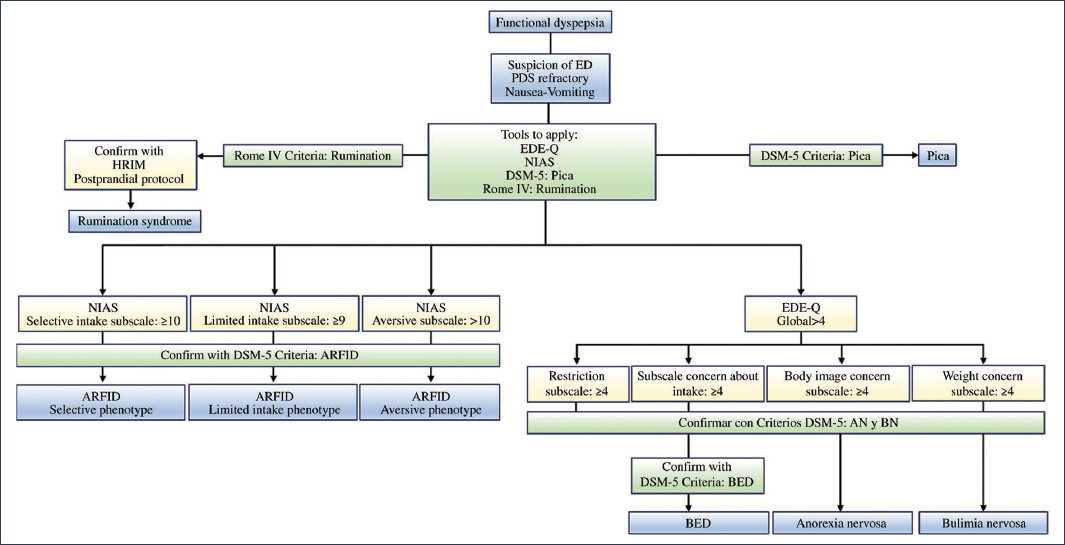

The diagnostic tools used in the approach to EDs in patients with FD are primarily based on questionnaires, with the exception of rumination, in which case high-resolution esophageal manometry with impedance is recommended, applying a solid food provocation test and postprandial assessment2,40,41. Screening questionnaires for EDs in patients with FD should be administered when the presence of these disorders is suspected, such as in cases of vomiting, cibophobia, clinical suspicion of rumination, or refractory PDS, especially if it presents as early satiety, with or without weight loss2 (Fig. 3).

Figure 3. Diagnostic tools used in the approach to eating disorders (ED) in patients with functional dyspepsia. AN: anorexia nervosa; ARFID: avoidant/restrictive food intake disorder; BED: binge eating disorder; BN: bulimia nervosa; DSM-5: Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 5th edition; EDE-Q: Eating Disorder Examination Questionnaire; HRIM: high-resolution impedance manometry; NIAS: Nine Item Avoidant/Restrictive Food Intake Disorder Screen; PDS: postprandial distress syndrome.

For the screening of ARFID, the Nine Item Avoidant/Restrictive Food Intake Disorder Screen (NIAS) questionnaire should be used; for rumination, the Rome IV criteria; for pica, the DSM-5; and for the remaining EDs, the Eating Disorder Examination Questionnaire (EDE-Q)2. In the event of positive screening for EDs, diagnostic confirmation of ARFID, anorexia nervosa, bulimia nervosa, or binge eating disorder should proceed using the DSM-5 criteria11 (Fig. 3).

Multidisciplinary approach and management

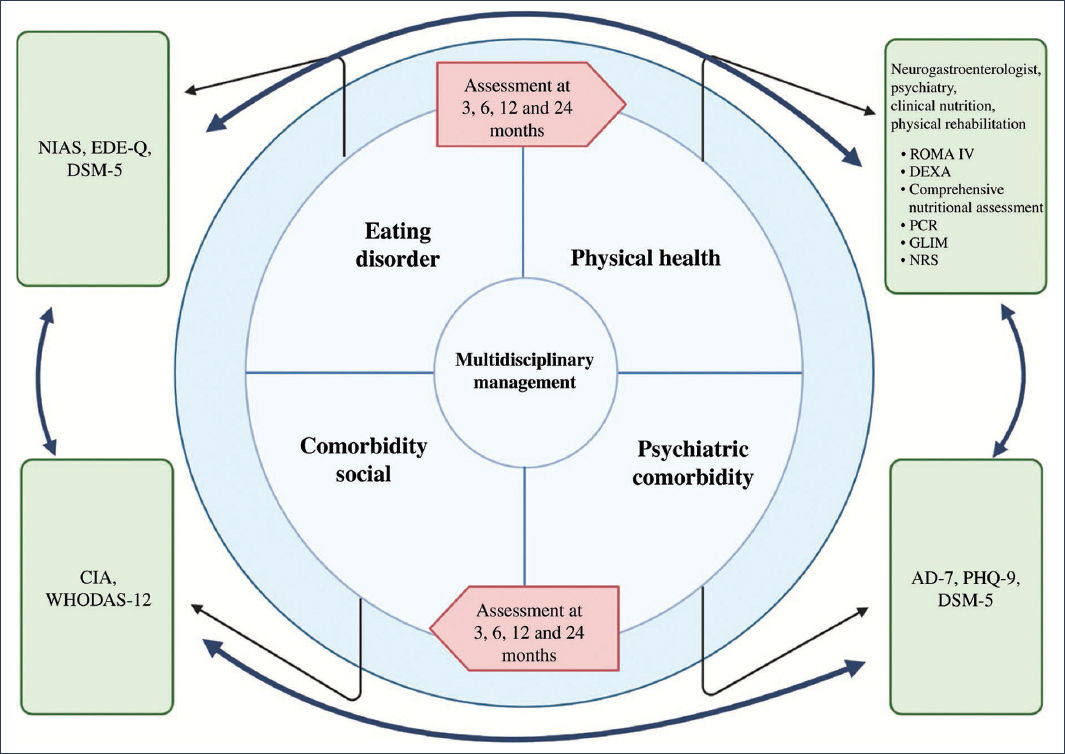

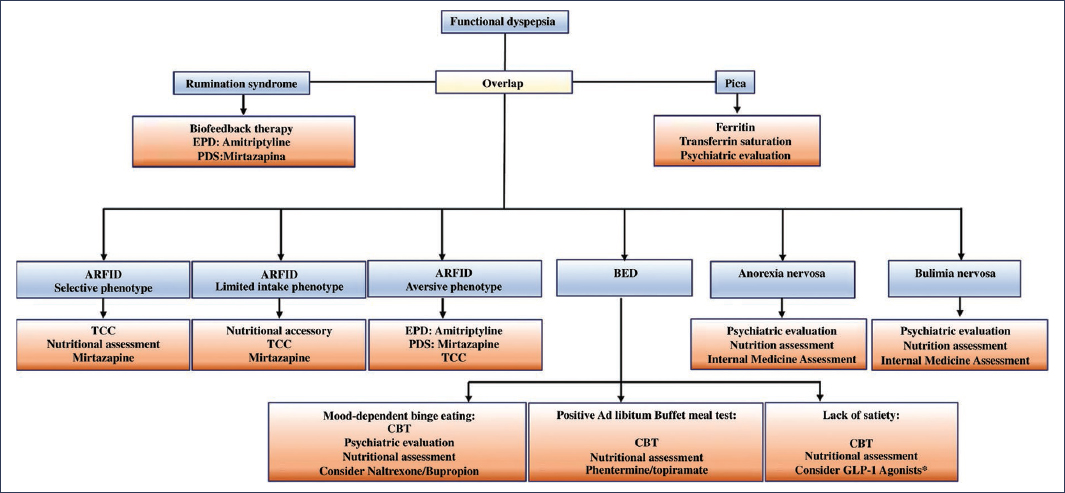

The approach and management of an overlap syndrome with EDs requires a holistic structure comprised of neurogastroenterology, psychiatry, psychology, and clinical nutrition. To determine the role of each specialist on the multidisciplinary team, a five-domain phenotype should be considered, consisting of the specific characteristics of the ED, the impact on physical health (disorders of gut-brain interaction [DGBI], malnutrition, etc.), psychiatric comorbidity, and social comorbidity (quality of life, impact on interpersonal relationships, etc.). Therefore, in all patients with EDs, the GAD-7 (7-item Generalized Anxiety Disorder Scale), PHQ-9 (9-item Patient Health Questionnaire), CIA (Clinical Impairment Assessment), and WHODAS-12 (12-item World Health Organization Disability Assessment Schedule) scales should be applied. The multidisciplinary assessment considering these five domains should be performed at baseline and at 3, 6, 12, and 24 months2. Management by the neurogastroenterology team focuses primarily on FD, and if neuromodulation is required, the pharmacological option with the best safety profile and dual effect on EDs, psychiatric comorbidity, and FD should be sought2,41 (Fig. 4). In rumination with FD, diaphragmatic breathing exercises guided by biofeedback are suggested, in conjunction with amitriptyline in cases of epigastric pain syndrome or with mirtazapine in PDS2,42,43. In ARFID with a selective or limited intake phenotype, the neuromodulator of choice is mirtazapine, but in an aversive phenotype secondary to epigastric pain syndrome, amitriptyline should be considered. In binge eating disorder, the phenotype of eating pattern, mood-dependent binge eating, absence of satiety, or high caloric intake requirement for satiety induction, assessed by the ad libitum buffet meal test, should be taken into account44. In patients with anorexia nervosa or bulimia nervosa, referral to psychiatry is suggested, regardless of the DGBI phenotype45,46 (Fig. 5).

Figure 4. Four domains for multidisciplinary approach and management. AD-7: 7-item anxiety and depression scale; CIA: clinical impairment assessment; DEXA: dual-energy X-ray absorptiometry; DSM-5: Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 5th edition; EDE-Q: Eating Disorder Examination Questionnaire; GLIM: Global Leadership Initiative on Malnutrition; HRIM: high-resolution impedance manometry; NIAS: Nine Item Avoidant/Restrictive Food Intake Disorder Screen; NRS: nutritional risk screening; CRP: C-reactive protein; PHQ-9: Patient Health Questionnaire-9; WHODAS-12: 12-item World Health Organization Disability Assessment Schedule.

Figure 5. Management strategies, including specialist assessment and neuromodulator of choice. ARFID: avoidant/restrictive food intake disorder; BED: binge eating disorder; EPS: epigastric pain syndrome; PDS: postprandial distress syndrome; CBT: cognitive-behavioral therapy.

Early detection in adolescents and young adults

Certain EDs, such as anorexia nervosa, typically manifest during adolescence, with a consistent pattern of onset before 14 years of age according to numerous studies47,48. EDs have been identified as more prevalent in populations with autism spectrum disorders; therefore, special consideration is recommended when screening this population group48. The importance of early detection of EDs is to prevent associated complications, such as increased suicide risk, non-suicidal self-injurious behaviors, kleptomania, substance abuse, and risky sexual behaviors, as well as physical complications with multiorgan involvement45,46.

Conclusions

Among the gastrointestinal symptoms identified in patients with EDs, symptoms within the dyspepsia spectrum have been the most frequently reported, with a prevalence that varies according to the type of ED. In the case of bulimia nervosa, these symptoms may occur in up to 83.3% of patients. A pathophysiological relationship has been established between FD and EDs, supported by shared mechanisms such as altered central processing, gastric dysmotility, and low-grade inflammation. This overlap generates a complex clinical syndrome that is difficult to diagnose and manage, as both conditions share symptoms that may be confused or overlapping, thereby delaying the implementation of effective interventions. This diagnostic difficulty is further compounded by factors related to communication and accurate interpretation of symptoms, which reinforces the need to apply specific diagnostic tools. The diagnosis and management of these overlapping syndromes must be approached in a multidisciplinary manner, with the participation of specialists in physical and mental health, evaluating the psychosocial environment and adjusting the intervention to the comorbidity identified in each patient. Likewise, periodic follow-up and timely diagnosis are essential to prevent associated complications and optimize clinical outcomes.

Funding

The authors declare that they have not received funding for this study.

Conflicts of interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Ethical considerations

Protection of human and animal subjects. The authors declare that no experiments have been conducted on human subjects or animals for this research.

Confidentiality, informed consent, and ethical approval. The study does not involve patient personal data nor does it require ethical approval. The SAGER guidelines do not apply.

Declaration on the use of artificial intelligence. The authors declare that they did not use any type of generative artificial intelligence for the writing of this manuscript.